Abigail Nalesnik, doctoral student in geology at the University of Delaware, looks through a rangefinder at the eruption in Kīlauea‘s Halema‘uma‘u crater the evening of September 30, 2021. She was on the first response team from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory to visit the eruption and helped make measurements of the active fountains and monitor the lava lake level to track how quickly it was rising. Photo taken from a closed area of Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park by Kendra Lynn, USGS.

“I was there when the volcano erupted.”

It is Wednesday, September 29, 2021, 3:21 p.m. Hawai‘i Standard Time (HST). Abigail Nalesnik is finishing up her fieldwork for the day. The University of Delaware doctoral student had been collecting samples of volcanic rock along a gully west of the summit of Kīlauea — one of the most active volcanoes in the world — working alongside Kendra J. Lynn, geologist for the U.S. Geological Survey and an affiliated professor at UD.

Then the alert came.

“There was an earthquake swarm under the summit, although we hadn’t felt anything,” Nalesnik said. “As we began driving from my field site, we saw the smoke rising out of Halema‘uma‘u crater. It was an amazing first view of a volcanic plume!”

Witnessing a volcano erupt is an unforgettable experience. And Kīlauea — one of the world’s youngest volcanoes, known to Hawaiians as the home of the revered goddess Pelehonuamea (Pele) — has offered up this incredible spectacle with some frequency. At this rupture in Earth’s crust, lava and gas have exploded from a magma chamber below the surface dozens of times since 1952 like a giant pressure cooker blowing its top.

Within minutes after seeing the plume, the USGS team began deploying to the eruption site in a closed area of Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park.

“We drove down an old portion of park road around the summit crater and began to study the fresh lava that had been thrown up and out of the crater,” Lynn said. “Now cooled, these freshly made rocks, ranging from a millimeter to 15 centimeters in diameter, were very vesicular – meaning they had a lot of gas bubbles – when they were quenched. These feather-light pumices were already rolling across the road and landscape, being buffeted about by the wind.”

ABOVE: Kendra Lynn, geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, collects fragments of rock, called tephra, ejected from the volcano. Photo courtesy of USGS.

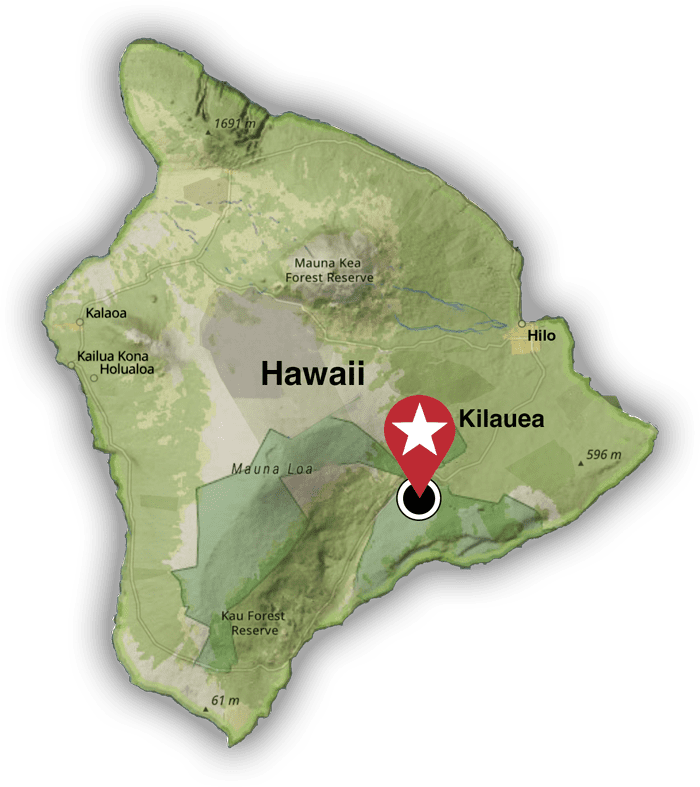

KILAUEA’S HALEMA’UMA’U CRATER

Where is Kīlauea volcano?

Kīlauea is the youngest and southeasternmost volcano on the island of Hawaii, which is known as the “Big Island” because it is larger than all of the other Hawaiian islands combined. It is also the largest island in the U.S.

How hot is erupting lava?

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, Kīlauea lava’s eruption temperature is about 1170° Celsius (2140° Fahrenheit). Once exposed to the air, the lava cools down quickly — by hundreds of degrees per second.

A rising lava lake

Since the 2021 eruption, lava in Halema‘uma‘u crater has risen 70 meters (230 feet) — that’s taller than a 20-story building. This molten rock, estimated at 10.5 billion gallons, would fill 200 million bathtubs — one for about every person in Brazil!

How many active volcanoes are there on Earth?

Most of the world’s volcanoes are underwater, on the ocean floor, where Earth’s tectonic plates — giant slabs of the planet’s crust — are being pulled apart. Outside of these, about 1,350 potentially active volcanoes exist around the globe, and about 500 are estimated to have erupted in human history. The Pacific Rim has so many volcanoes it is known as the “Ring of Fire.”

KILAUEA’S HALEMAUMAU CRATER

Where is Kilauea volcano?

Kilauea is the youngest and southeasternmost volcano on the island of Hawaii.

How hot is erupting lava?

The eruption temperature of Kilauea lava is about 1,170 degrees Celsius (2,140 degrees Fahrenheit) but the outer surface of erupting lava cools incredibly quickly (by hundreds of degrees per second) when first exposed to air.

40 million cubic meters and counting

According to a USGS report on Jan. 13, 2022, Halemaʻumaʻu lake had seen a total rise of about 70 meters (230 feet) since lava emerged on September 29, 2021. Measurements on December 30, 2021, indicated that the total lava volume effused since the beginning of the eruption was approximately 40 million cubic meters (10.5 billion gallons) at that time.

How many active volcanoes are there on Earth?

There are about 1,350 potentially active volcanoes worldwide, aside from the continuous belts of volcanoes on the ocean floor at spreading centers like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. About 500 of those 1,350 volcanoes have erupted in historical time.

Q: What does an erupting volcano sound like?

ABOVE AUDIO: Sounds of lava lake activity within Kīlauea volcano’s summit vent inside Halema‘uma‘u crater on February 14, 2011. Courtesy U.S. Geological Survey.

Lynn was impressed by the sound of the rocks and particles called tephra being ejected from the volcano.

“The rolling clasts made a light ‘tink, tink, tink’ that made me instantly think of Christmas ornaments. When the wind gusts died down, there was an incredible sloshing sound, like waves on a beach. This was the lava and the active eruption, which was out of sight deep in the crater beyond where we were working.”

Nalesnik will never forget the sound of the lava fountains.

“Somewhat like very heavy water splashing down onto the lava lake, but unlike anything I’ve heard before. You could hear the fountains without being very close to the edge of the crater.”

Q: And what about the smell?

“Not fantastic,” Nalesnik said, due to the sulfur dioxide, which smells like burnt matches. What’s more, sulfur dioxide irritates the eyes, nose and throat, causing you to cough and have a tight feeling in the chest. Headache, nausea, fatigue are other effects. Thus, gas masks were necessary to be in the area. But the view more than made up for it.

“Arriving at the edge of the crater to do measurements, the glow of the lava lake was surreal, with each small fountain and bubble of lava a fiery orange-red.”

Q: What do you wear working near a volcano?

With the eruption occurring deep inside Halema‘uma‘u crater, the researchers monitored the event from a distance and were not close enough to sample the lava. Still, they could feel the heat due to the vast size of the lava lake — estimated to be 70 floors deep if the Empire State Building were plopped into it.

“You can feel the heat on your face, but it is surprisingly chilly at the summit with the strong winds,” Nalesnik said.

Each team member wears a respirator, a critical piece of personal protective equipment (PPE) that must be worn when sulfur dioxide is present, Lynn said. They also wear an electronic gas badge calibrated to vibrate and beep to signal the concentration levels of sulfur dioxide, so they can quickly get out of areas inundated with gas. Other essentials include high-visibility uniforms, hard hats, cotton pants (synthetic materials melt when close to an active lava field), sturdy leather boots, and when windy, goggles to protect the eyes from blowing ash.

and why is it important?

Volcanoes are among Nature’s greatest wonders, but they also can be extremely dangerous. Kīlauea’s eruption in 2018 caused evacuations in residential areas southeast of Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park, as fissures opened up in the Earth’s crust — some 22 of these long, narrow cracks — and the large flows of lava destroyed more than 700 homes, as well as roads, schools and businesses. For months, residents downwind had to wear N95 masks to protect themselves from toxic ash and sulfur dioxide gas.

The scientists at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) have wide-ranging skills for studying such an explosive phenomenon. As a field geologist, Lynn works with her team to monitor the eruption on site. In addition to a permanent network of time-lapse and networked cameras, they capture the volcanic activity with high-resolution photographs and videos. They also use a rangefinder to measure the height of the lava lake and other features in the crater, which helps them to make important calculations such as lava fountain heights and effusion rates, which might increase if an eruption is gaining intensity or decrease if an eruption is waning.

Lynn is also a petrologist — a scientist who studies the composition, texture and structure of rocks and minerals to understand how and when they formed — so she collects samples of tephra and olivine, a mineral rich in iron and manganese, for polishing and chemical analysis back in the lab. Olivine can provide clues as to when and where the magma was stored in the volcano prior to the eruption.

“I look for patterns in the chemistry of erupted lavas that might help us to understand how the volcano behaves over decades to centuries,” Lynn said. “This might give us a better idea of what to expect in the future and be better prepared for the hazards associated with such events. In general, our monitoring observations help assess hazards and risk in real time, and the information allows the National Park Service and other agencies to make decisions.”

Q: What’s the most surprising thing about

working around an active volcano?

“I was surprised at how much there is to do!” Nalesnik said. “There are various specialties at HVO, such as the gas team that measures the volcano emissions, the seismology team that monitors the earthquakes, and of course the geology team that studies the physical deposits. These and several other teams have so many different avenues for study and analyses that reflect on different aspects of the volcano. It was great to see them all working together to navigate this current eruption and learn all that we can.”

For Lynn, the sheer scale of Earth’s outburst never gets old.

“I am shocked every time I see an eruption at how big it is — that we can have fountains of lava over 60 feet tall — that’s taller than a four-story building!”

Q: Where does this experience rank on your geo-bucket list?

“Participating in an active eruption response was definitely #1 on my bucket list!” said Nalesnik, who had received funding from the National Science Foundation to do work at the site for her UD doctoral research under the guidance of her adviser, Professor Jessica Warren. “Driving from my field site, seeing the plume rising out of Halema‘uma‘u, feeling so excited and nervous, will be a memory I keep for the rest of my life. As volcanoes are such dynamic landforms, I am thankful I had my gear packed and was prepared in case something happened during my short visit. Five weeks isn’t a very long time.”

For Lynn, Kīlauea has always been a very special place. “Growing up, I dreamed of studying it, and when I finally got that opportunity in graduate school, visiting the volcano changed my life forever,” she said. “Kīlauea is my favorite place on Earth, and is also a special and sacred place in Hawaii, home to Pelehonuamea, goddess of the volcano. As a guest in Hawaii and at Kīlauea, I am constantly in awe of Pele.”

Cool paths to a hot field

Abigail Nalesnik

Ph.D. Student,

Department of Earth Sciences, University of Delaware

When I was a kid, I was fascinated with what was beneath my feet. I loved to dig holes to look at soil horizons and had my face glued to the car window when driving past uplifted rocks of unknown age or origin. Everything was a mystery to me. I was fascinated by it all and knew that the science behind inner Earth was for me. I explored sedimentary rocks and soil, but realized that I kept going back to the beginning … where did it all come from? And thus, I learned about plate tectonics and active volcanoes!

What advice do you have for young students who aspire to be geologists?

Geology is not just the minerals, sediments, rocks or formations. It is the processes and experiences and lives of Earth materials that are far older than is fathomable. There are so many fields of study within geology, you just need to find what you’re interested in and run with it. Little me in second-grade reading about volcanoes had no idea that we would be a part of an eruption response for one of the most active volcanoes in the world.

Kendra J. Lynn

Geologist,

Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, U.S. Geological Survey; Affiliated Professor, University of Delaware

I have been fascinated by volcanoes my entire life — I was 5 years old when I decided I wanted to be a volcanologist. In college, I fell in love with Earth sciences more broadly and enjoyed research projects in soil science for an organic farm and then metamorphic geology in New England. I was 20 when I finally saw my first volcano — I did a university travel study in Costa Rica and stood in the shadow of Arenal. I knew then that I was meant to do this — it reinforced everything I’d been feeling for about 15 years.

Volcanology — and Earth science — is inherently interdisciplinary, which I think is the greatest scientific freedom of this job. You can pursue the topics that fascinate you and dabble in chemistry, physics, space science, mathematics, biology and computer coding (to list only a few subjects!) to better understand geologic processes on Earth and other planets. There is something here for everyone — and everyone has a place in Earth science.

“I am shocked every time I see an eruption at how big it is — that we can have fountains of lava over 60 feet tall — that’s taller than a four-story building!”

— Kendra J. Lynn

What is a volcano anyway?

MORE STORIES

Life Cycle of a Fact

Is there any such thing as a fact? Who and what can we trust these days? Here’s the method to stem the madness.

Adding Peril to a Pandemic

As our world continues its struggle against the COVID-19 pandemic, another global threat has proven tougher to arrest, just as lethal and likely to be a key factor in crises to come.

Getting the Message Right

It’s a problem almost as old as time: You think your words are clear, but your audience seems to hear something different than you intended—or worse, they don’t really hear you at all.

What Happens When Communication is Blocked?

Professor Isaí Jess Muñoz has produced an award-winning recording of the music of a once-repressed region of Spain.

Test Your Knowledge

How much plastic is around us and how can we stem the plastics pollution problem? Take the quiz!

Research Leadership Announced

Kelvin Lee has been appointed interim vice president for research, scholarship and innovation at UD.

Celebrating Excellence

Check out the UD faculty and students who have won national recognition for their expertise and contributions.

News Briefs

Did you know the world’s longest-operating solar research institute is at UD? Or that some old books could be poisonous? Tap into our recent discoveries and leadership appointments.