That’s why more than 60 young figure skaters—including five of the six singles skaters on the 2018 U.S. Olympic Team and five of the six alternates—have made their way to the University of Delaware’s ice rinks over the past decade. Prompted by the U.S. Figure Skating Association and their coaches, they hope to gain a competitive edge through a unique biomechanical analysis done by Jim Richards, distinguished professor of kinesiology and applied physiology in the College of Health Sciences.

Richards and his research team have rigged up an array of 10 cameras that capture data from reflective markers placed on skaters. As they attempt challenging jumps—especially the triple Axels, quadruple jumps and jump combinations that put elite skaters at the top of their sport—the cameras record their precise positions, the speed of their rotations, their time in the air. The data are then fed into a computer program Richards developed with biomechanics expert Tom Kepple, chief science officer at C-Motion Inc. and a former UD instructor.

Researchers aren’t looking at fancy footwork sequences or scratch spins or any of the other elements of competitive skating.

“We’re only looking at what they’re doing in the air,” Richards said. “Almost every skater has the rotational energy to complete the jump. It’s what they’re doing in the air that keeps them from being successful.”

Consider that the triple Axel requires three full rotations in the air and a quadruple jump requires 3 1/2. That’s 1,080 degrees of rotation (360 x 3) for the Axel, 1,260 for a quad.

“They have to get into their tightest position within a specific time period,” Richards said. “For a triple or quad, that’s within the first revolution.”

Rotation speed is lost if an arm is sticking out a bit or their head is leaning. And the cameras don’t lie.

The adjustments aren’t easy for skaters, Richards said, but the science is persuasive.

Debbie Minahan, who coaches skater Will Annis at the Yarmouth (Mass.) Ice Club, often uses video to analyze skaters’ techniques but was excited to have access to this level of analysis.

“I thought this was an incredible opportunity that wouldn’t be offered anywhere else,” she said. “For Will—working on all of his triples now—it seemed that it would be valuable to have that feedback.”

researchers onto an idea that could be of great value to cancer researchers.

The collaboration of Prof. Prasad Dhurjati, a chemical engineer who has done extensive computer modeling of biological and engineering systems, and Prof. Deni Galileo, a neurobiologist whose expertise is in cell motion and behavior in the brain, has produced a new and freely available computer program that predicts cancer cell motion and spread with high accuracy.

Galileo has been studying the movement and spread of glioblastoma tumors— an aggressive and devastating form of brain cancer that has claimed thousands of lives, including those of Delaware Attorney General Beau Biden, U.S. Sen. Ted Kennedy and two Phillies greats—pitcher Tug McGraw and catcher Darren Daulton—to name just a few. U.S. Sen. John McCain was diagnosed in 2017.

A significant challenge rests in the fact that this cancer spreads rapidly, reducing the effectiveness of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation. Dhurjati looked at Galileo’s work and realized it was a strong candidate for the kind of mathematical modeling he does with biological systems. Together, they constructed a computer model of glioblastoma cells that accurately reflects what Galileo sees live cells doing under a microscope. And that opens new opportunities for researchers.

“When your model represents real systems, you can play with the model in ways you cannot play with a human brain,” Dhurjati said. The new model can be adapted to help researchers looking at other kinds of cells, too, and is ideal for education purposes.

“We are not interested in stopping cells in a dish, but in a brain,” Galileo said. “Ultimately we want to model the total three-dimensional behavior of how cells move around.”

Watch our Research and Discovery Playlist

That’s one of the key findings made by Kyle Emich, assistant professor of management in UD’s Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics, with co-authors from the University of Arizona, Boston College and the United States Military Academy, in their article for the Academy of Management Journal.

“In sum, we find that when men speak up with ideas on how to change their team for the better they gain the respect of their teammates—since speaking up indicates knowledge of the task at hand and concern for the wellbeing of the team,” Emich said. “Then, when it comes time to replace the team’s leader, those men are more likely to be nominated to do so. Alternatively, when women speak up with ideas on how to change the team for the better, they are not given any more respect than women who do not speak up at all, and thus are not seen as viable leadership options.”

Emich said that in the case of the researchers’ first sample, involving military cadets at West Point, “This difference is immense.”

On average in 10-person teams, men who speak up more than two-thirds of their teammates are voted to be the No. 2 candidate to take on leadership. Women who speak up the same amount are voted to be the No. 8 candidate. “This effect size is bigger than any I have seen since I began studying teams in 2009,” Emich said.

Further, in a lab study of working adults from across the U.S., Emich said, “We find that men are given more credit than women even when saying the exact same thing.”

Correcting the problem will take effort and conscious attention to biases against women.

“We all use cognitive shortcuts to get through each day,” Emich said. “Think of what you had for breakfast. You probably just grabbed the closest thing to you, or followed a pattern of what you always eat. Well, we have patterns and shortcuts involving people too, and one of them is more easily considering men leaders even when women exhibit the exact same behaviors. And this shortcut has very real negative consequences for women and workplaces alike.”

Now, a fund established in his memory and dedicated to his goal of improving diversity in the field of disaster studies has found a home at the University of Delaware.

Anderson, who died in 2013, had longstanding ties to UD’s Disaster Research Center (DRC) and was among the center’s first doctoral students when it was founded in 1963 at Ohio State University. (It moved to UD in the 1980s.)

His widow, Norma Anderson, created the nonprofit Bill Anderson Fund (BAF) in 2014. With what she called “a groundswell of support” from her husband’s many former colleagues, students and protégés, BAF has gone on to provide graduate students across the U.S. with assistance in building careers in disaster research and practice.

“We have a wonderful and very forward-thinking board of directors, and we’ve been very active in holding workshops and mentorship programs,” Norma Anderson said. “But my ultimate goal was always to have the Bill Anderson Fund housed at a university, and to have a director who was an academic.

“I am so thrilled that we’re going to be at the University of Delaware. Bill was in the first cohort of the Disaster Research Center, so in many ways we see him returning to his professional home.”

Dr. William Averett Anderson

William Averette Anderson earned his doctorate in sociology at Ohio State University in 1966 and went on to a career as a college professor, a National Science Foundation (NSF) officer, a World Bank natural disaster specialist and an official of the National Research Council.

He was known as a pioneering researcher and a leader in fostering student learning and in mentoring the next generation of disaster scholars.

As a professor at Arizona State University, he directed the American Sociological Association’s minority fellowship program. Later, at NSF, he promoted studies of the effects of disasters on vulnerable populations.

“Our partnership with Nuvve Corporation demonstrates the University of Delaware’s abiding commitment to cutting-edge research and innovation. This collaboration opens up new horizons for synergizing the strengths of academia and industry in charting the future of clean and sustainable energy,” UD President Dennis Assanis said. “The University of Delaware’s students and researchers are—and will continue to be—a major force in the global transportation revolution.”

Nuvve, a Delaware company based in California, gained exclusive global rights to market UD’s pioneering vehicle-to-grid technology (V2G) in 2016. Electric vehicles with the UD technology can charge or discharge their batteries back to the electric grid. The software aggregates all vehicles plugged into the system so that they perform in unison, helping to balance the grid’s supply of electricity with demand—in real time, on a second-to-second basis. Conventional power plants take several minutes to respond to grid demands.

Under the new agreement, Nuvve will hold the patents to the V2G technology and UD will hold an equity share in the company. Additionally, UD will establish an advanced R&D center to expand its leadership in the technology.

“A major transition is underway in the world, and the University of Delaware is right at the forefront,” said David Weir, director of UD’s Office of Economic Innovation and Partnerships. “The technology pioneered here at UD will further accelerate the disruption that’s taking place and shake up the transportation marketplace.”

MORE STORIES

2017 Research in Progress

What’s it like to do research in the Arctic? What ‘s it like to be on a ship for 4 to 6 weeks off Greenland? How do you work and sleep with 24 hours of daylight? Oceanographer Andreas Muenchow gives us a glimpse into his world.

At Sea in the Arctic

What’s it like to do research in the Arctic? What ‘s it like to be on a ship for 4 to 6 weeks off Greenland? How do you work and sleep with 24 hours of daylight? Oceanographer Andreas Muenchow gives us a glimpse into his world.

The Quiet Revolution

Trevor A. Dawes learned how libraries can change people’s lives when he was a college student. Now, he’s leading the charge to make the UD Library, Museums and Press an even greater force for good.

The hidden lives within a portrait

A 1746 portrait would launch a global journey into 18th-century life and present the past in a way never done before. The portrait was of Anne Shippen Willing, and what she wore would lead historian Zara Anishanslin on a journey to the far corners of the world—and launch a bold new way of looking at the past.

Filling a Real Demand for Simulated Care

Nursing instructor Amy Cowperthwait and her students are inventing products with a common goal: teaching compassionate patient care. Cowperthwait’s startup links students, engineers, business experts on quest to teach challenging medical procedures.

Suit Me Up for Mars

When astronauts make the “Journey to Mars,” NASA wants every protective measure available in place. The space agency contracted with ILC Dover to develop a new spacesuit, and ILC enlisted several materials experts at the University of Delaware to work on a suit that can handle whatever space might throw at them.

A NIIMBL Approach To Making Modern Medicines

Biopharmaceuticals have emerged recently and are having a revolutionary impact on vexing diseases such as cancer. The National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL), headquartered at the University of Delaware, is at the forefront of making medicines more accessible to Americans.

Exploring the Red Planet

NASA wants to put humans on Mars by the early 2030s. University of Delaware researchers are helping to develop spacesuits for that mammoth expedition. Yet Mars is shrouded in mystery for many of us. So what do you know about Mars? Let’s test your knowledge.

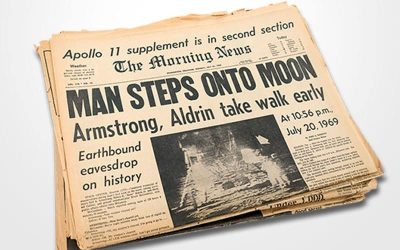

1969 – The Morning News: Man Steps onto Moon

Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong took the first moon step at 10:56 p.m., Delaware time, just six hours and 39 minutes after he and Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. fulfilled the age-old dream of landing on the moon. This was a major milestone in the new era of space exploration. We invite you to explore this interactive experience and relive the excitement of the first moon landing.

Partnerships in progress

Multiple partnerships took wing in the past year to ensure UD’s scholarly efforts have the broadest and most sustained impact. Learn about the collaborations that ensure a UD world-class educational experience while serving as a major force for economic development.

Honors

Eight UD professors recently received the National Science Foundation’s highly competitive CAREER Award, which is given to scientists and engineers who exemplify the role of teacher-scholars through their outstanding research and teaching.