No, she’s not a chef for Count Dracula. She’s a clinical nurse specialist in the University of Delaware’s Nursing Resource Simulation Center, and she has been cooking up packs of the plasma-like product to help nursing students, medical technicians and others learn the art of drawing blood.

It will be part of a kit her new company—Avkin—produces to help learners practice such procedures in realistic ways using silicon “skin” that has similar resistance to a needle, for example, and this fake blood that is drawn into an intravenous catheter just as real blood would be in a clinic.

With such experience, her UD students enter clinical settings with much greater confidence and skill. They are far less likely to be the “night nurse from hell” that one tracheostomy patient described to Cowperthwait—doing suction procedures that went too deep, went on too long and did way too much.

“If that nurse could just get re-trained and hear about their patient’s experience, I am 100 percent positive they would change their care,” Cowperthwait said.

Avkin (formerly known as SimUCare) is one of a growing number of success stories emerging from UD’s Office of Economic Innovation and Partnerships, which shepherds viable new products developed by faculty and students to the marketplace.

Cowperthwait’s work was fueled by grants and prizes as products were developed and tested and the company was named one of the best startups in the nation by the National Council for Entrepreneurial Tech Transfer in 2016. A business investor has added fresh vigor to the company’s growing list of products.

From simulated tracheostomy care (Avtrach) to drawing blood (Avstick) and urinary catheter placement (Avcath), Avkin has a list of seven devices either on the market, in final testing or in various stages of development. All have emerged from UD engineering students’ senior design projects—a partnership Cowperthwait hopes to continue as new prototypes emerge.

The new devices and the simulation technology embedded within them are unique, even more so when worn by students enrolled in a course taught by faculty in UD’s Healthcare Theatre, a program Cowperthwait co-founded with Allan Carlsen of the Department of Theatre. Students practice on these actors, who respond in real time to haptic signals, such as vibrations, from electronic sensors.

The devices may indicate that excessive force has been used, for example, and the actor may holler “Ouch!” The devices have anatomically correct features. They produce sounds—and sometimes smells—that correspond to those typical to the situation. It can get intense.

“I’ve been on both sides of the simulation,” said C Pat Lombardi, who got his bachelor’s degree in biology at UD and just received his bachelor’s in nursing through the University’s accelerated nursing program. “On the acting side I had anxiety—would I say the right thing? Would I make it difficult enough, but not too difficult?

“And on the other side of the coin, as a nurse, am I going to remember to scrub the top of the needle? Can I assess the sterile procedure? I can absolutely see how bedside manner can be lost. You have a checklist in your mind. You have to manage the bedside manner but still get what you need to do done.”

Consider what nurses and patients face in tracheostomy care, as an example. A tracheostomy patient breathes through a tube that is surgically placed in the throat and must be cleared periodically using suction.

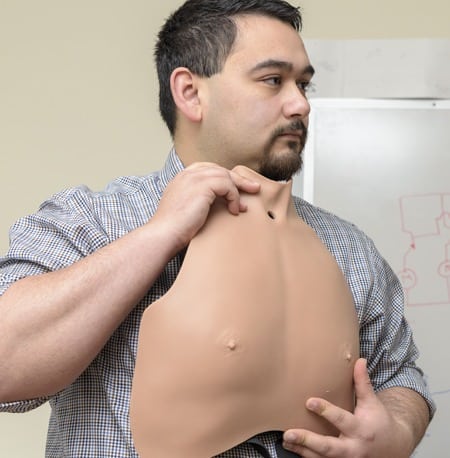

ABOVE AVTRACH: Medical caretakers can learn and build skills in tracheostomy care using this Tracheostomy Care Overlay System. It is designed as a man’s chest with a portal at the base of the throat, where tubing for suctioning and other procedures is inserted.

AT RIGHT: 1 & 2. ENGINEERING POWER: Matthew Eizardo (above right) worked on Avtrach development as an engineering student and now is one of Avkin’s full-time staff members. 3. HANDS-ON TRAINING: Nursing students Jerelene Thorpe (left) and Cory Haaf (right) were among the first to practice tracheostomy care in a unique way in 2016—using the lifelike Avtrach device, worn by volunteer “patient” Robert Tilley (center) .

“Plus, it’s an unnatural hole and it’s an uncomfortable position to be in. You don’t want to hurt this person.”

Avtrach is shaped as a man’s chest with a portal at the base of the throat, where tubing for suctioning is inserted.

“When the suction catheter goes down too far, it buzzes and tells the person who’s wearing the piece when to act like they’re having trouble,” said Cory Haaf, who graduated from UD’s School of Nursing in 2016.

Lombardi said the simulation practice gave him much greater confidence when he encountered his first tracheostomy patient during clinical studies at Christiana Care Hospital. The procedure went well and he credits his clinical instructor and his experience in UD’s simulation lab.

Haaf agreed.

“When I finally saw it in person in the hospital—it looked exactly like it did in the lab,” he said.

Haaf and Lombardi both have worked as emergency medical technicians with Aetna Hose, Hook and Ladder Company in Newark. They believe the devices would be helpful training for other emergency medical responders, as well as physicians and a broad range of health care workers. Family caregivers, too, can learn the procedures they must perform for loved ones at home—reducing their stress and that of the patient.

“I saw so many new nurses who had solid technical skills struggle with the real-life matter of caring for the person behind the critical need and their family. What was missing in their education? The human element,” she said. “Nursing students were learning medical procedures on plastic models but not the interaction challenges of communicating with live human patients during their times of greatest need.”

Nurses face many situations that make communication challenging. They must be able to speak with patients who are awake but nonverbal, for example, Cowperthwait said. And a new 21-year-old nurse must know how to talk to a 45-year-old about his or her sexuality, which may be an important factor in that patient’s care.

“If you’re not comfortable doing that, the patient will not be comfortable either,” she said. “The quality of communication and the quality of care have a direct impact on patient outcomes.”

Learning to insert urinary catheters is “socially uncomfortable,” Lombardi said. He wishes he had had that simulated experience when he had to place a catheter in a real patient the first time.

“The first time I put in a catheter, the patient was a woman who had just given birth,” he said. “It was a miracle that she allowed me into the room, let alone let me place a straight catheter.”

It went well, he said, “but I was nervous. The nurse I was with was incredibly helpful, but I can say I would have been more comfortable if I had had the [simulation] training.”

The School of Nursing’s Resource Simulation Center exists to help students learn what to say, what to ask, how to respond.

None of this machinery was in Cowperthwait’s Plan A when she joined UD’s faculty in 2006 after 28 years as an emergency-room nurse. But innovation happens.

“You grab a tiger by the tail and hold on tight,” she said—and you let others do what they do best.

“It’s really good to get nurses and engineers together,” Cowperthwait said. Add the theatre students and you have “beautiful, beautiful synergy” and a great environment for innovative ideas and solutions.

For expertise in design, manufacturing, business practice and marketing, she worked with mechanical engineering students and faculty, including Jenni Buckley and Liyun Wang of the College of Engineering, and had guidance from Joy Goswami, assistant director of the Tech Transfer Center in OEIP, in addition to UD’s Horn Program in Entrepreneurship, the Delaware Biotechnology Institute and the Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics.

Since Avkin’s launch in 2016, the back room of its New Castle, Delaware, headquarters has morphed into a small-but-intriguing makerspace, where rubber tubing and bits of silicon, razor knives, bubble wrap and assorted adhesives are stocked beside red dyes, hypodermic needles and a plastic tub used when cooking up synthetic blood.

It now has seven full-time employees and five part-timers. “We see our relationship with the University as not ending,” Cowperthwait said. “We will always start our product development through the University’s senior design program. The company’s founders believe in education and there is a symbiotic relationship. We have theatre, nursing and engineering students working together—where does that even happen? We will keep innovating and moving forward.”

And patients and their caregivers will reap the rewards.

“I saw so many new nurses who had solid technical skills struggle with the real-life matter of truly caring for the person behind the critical need and their family. What was missing in their education? The human element.”

—Amy Cowperthwait, Founder & CEO, Avkin

MORE STORIES

2017 Research in Progress

What’s it like to do research in the Arctic? What ‘s it like to be on a ship for 4 to 6 weeks off Greenland? How do you work and sleep with 24 hours of daylight? Oceanographer Andreas Muenchow gives us a glimpse into his world.

At Sea in the Arctic

What’s it like to do research in the Arctic? What ‘s it like to be on a ship for 4 to 6 weeks off Greenland? How do you work and sleep with 24 hours of daylight? Oceanographer Andreas Muenchow gives us a glimpse into his world.

The Quiet Revolution

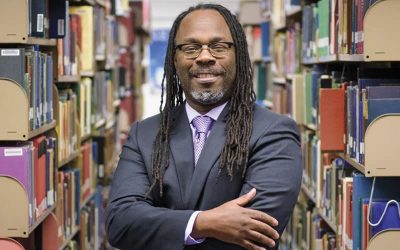

Trevor A. Dawes learned how libraries can change people’s lives when he was a college student. Now, he’s leading the charge to make the UD Library, Museums and Press an even greater force for good.

The hidden lives within a portrait

A 1746 portrait would launch a global journey into 18th-century life and present the past in a way never done before. The portrait was of Anne Shippen Willing, and what she wore would lead historian Zara Anishanslin on a journey to the far corners of the world—and launch a bold new way of looking at the past.

Suit Me Up for Mars

When astronauts make the “Journey to Mars,” NASA wants every protective measure available in place. The space agency contracted with ILC Dover to develop a new spacesuit, and ILC enlisted several materials experts at the University of Delaware to work on a suit that can handle whatever space might throw at them.

A NIIMBL Approach To Making Modern Medicines

Biopharmaceuticals have emerged recently and are having a revolutionary impact on vexing diseases such as cancer. The National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL), headquartered at the University of Delaware, is at the forefront of making medicines more accessible to Americans.

Exploring the Red Planet

NASA wants to put humans on Mars by the early 2030s. University of Delaware researchers are helping to develop spacesuits for that mammoth expedition. Yet Mars is shrouded in mystery for many of us. So what do you know about Mars? Let’s test your knowledge.

1969 – The Morning News: Man Steps onto Moon

Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong took the first moon step at 10:56 p.m., Delaware time, just six hours and 39 minutes after he and Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. fulfilled the age-old dream of landing on the moon. This was a major milestone in the new era of space exploration. We invite you to explore this interactive experience and relive the excitement of the first moon landing.

News Briefs

Learn how UD researchers are sharpening that competitive edge, fighting brain cancer, giving credit where credit is due, partners in disaster research and UD-NUVVE collaboration

Partnerships in progress

Multiple partnerships took wing in the past year to ensure UD’s scholarly efforts have the broadest and most sustained impact. Learn about the collaborations that ensure a UD world-class educational experience while serving as a major force for economic development.

Honors

Eight UD professors recently received the National Science Foundation’s highly competitive CAREER Award, which is given to scientists and engineers who exemplify the role of teacher-scholars through their outstanding research and teaching.