Anishanslin, assistant professor of history and art history at the University, first fell under Mrs. Willing’s gaze at Winterthur Museum while completing a project on early American style for her doctorate in history, which she received in 2009.

“You can’t miss her,” says Anishanslin, whose assignment was to sketch a piece of furniture in the room. “Her dress actually matches the furniture quite nicely.”

Fast-forward two years, and imagine Anishanslin’s surprise during a visit to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London when she spotted the original watercolor of that flamboyant floral pattern from Mrs. Willing’s silk dress.

“I knew I had seen it before,” she says, and then remembered where. Intrigued, she returned to Winterthur and sought out all the information she could find on the painting.

The book reveals insightful details about the four individuals whose lives intertwined within a silk dress, as well as the history of early America, trade, women’s roles, slavery and the colonies’ relationship with the rest of the world.

Because few letters, diaries or other historical documents remain to tell their stories, Anishanslin focused on what does exist—the visual material—to recreate her subjects’ lives. The work took her to unexpected places.

“Textiles are so closely linked to the human body,” she says. “Imaginatively reconstructing the past through what people wore is an intimate thing.”

Anna Maria Garthwaite, the designer who created the vivid floral pattern, was from Spitalfields—the silk-weaving center in London’s East End. Her work was a subject of national pride in an ongoing battle for superiority between English and French silk designers.

Simon Julins, the London weaver who made the silk cloth, lived only two blocks from Garthwaite’s townhouse and both were longtime members of the congregation of Christ Church Spitalfields. (As part of her research, Anishanslin even asked the current owner of Garthwaite’s house if she might see inside, which the owner graciously allowed.)

New England painter Robert Feke must have been proud of his portrait of Mrs. Willing because he signed it. After all, Anishanslin found, Feke applied his signature to only a handful of works.

As Anishanslin unearthed and pieced together “bits of archival detritus,” she had to take a leap of faith now and then. “You can’t go down every rabbit hole, or you will never get out.”

She also says she couldn’t have accomplished her detective work without the assistance of generous museum curators, librarians, even an apothecarist.

“Research is a really solitary thing,” she says, “but it is a group effort as well. You need to rely on the kindness of strangers and great fellowship.”

Anishanslin says the moral of her story is that we should visit museums and really think about what we see.

“When you look at a portrait, it’s not just a portrait,” she says. “There are all of these really fascinating stories embedded in each object.”

WHAT HAPPENED TO ANNE?

She was 36 when her portrait was painted. Eight years later, her husband died unexpectedly of a fever when their youngest child was only a toddler. She never remarried. She eventually moved out of her sizable house and lived with an unmarried daughter, Abigail, in a small house on Pine Street in Philadelphia until her death at 81.

Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Portrait of Anne Shippen Willing (Mrs. Charles Willing), 1746, Philadelphia, PA, Oil paint on canvas, Museum purchase with funds provided by Alfred E. Bissell in memory of Henry Francis du Pont, 1969.134

MORE STORIES

2017 Research in Progress

What’s it like to do research in the Arctic? What ‘s it like to be on a ship for 4 to 6 weeks off Greenland? How do you work and sleep with 24 hours of daylight? Oceanographer Andreas Muenchow gives us a glimpse into his world.

At Sea in the Arctic

What’s it like to do research in the Arctic? What ‘s it like to be on a ship for 4 to 6 weeks off Greenland? How do you work and sleep with 24 hours of daylight? Oceanographer Andreas Muenchow gives us a glimpse into his world.

The Quiet Revolution

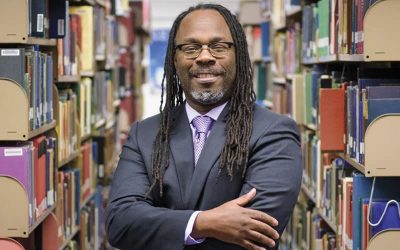

Trevor A. Dawes learned how libraries can change people’s lives when he was a college student. Now, he’s leading the charge to make the UD Library, Museums and Press an even greater force for good.

Filling a Real Demand for Simulated Care

Nursing instructor Amy Cowperthwait and her students are inventing products with a common goal: teaching compassionate patient care. Cowperthwait’s startup links students, engineers, business experts on quest to teach challenging medical procedures.

Suit Me Up for Mars

When astronauts make the “Journey to Mars,” NASA wants every protective measure available in place. The space agency contracted with ILC Dover to develop a new spacesuit, and ILC enlisted several materials experts at the University of Delaware to work on a suit that can handle whatever space might throw at them.

A NIIMBL Approach To Making Modern Medicines

Biopharmaceuticals have emerged recently and are having a revolutionary impact on vexing diseases such as cancer. The National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL), headquartered at the University of Delaware, is at the forefront of making medicines more accessible to Americans.

Exploring the Red Planet

NASA wants to put humans on Mars by the early 2030s. University of Delaware researchers are helping to develop spacesuits for that mammoth expedition. Yet Mars is shrouded in mystery for many of us. So what do you know about Mars? Let’s test your knowledge.

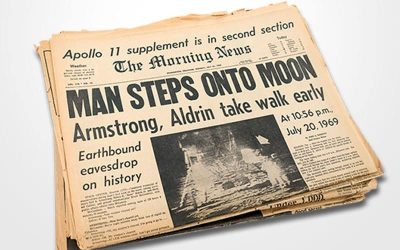

1969 – The Morning News: Man Steps onto Moon

Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong took the first moon step at 10:56 p.m., Delaware time, just six hours and 39 minutes after he and Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. fulfilled the age-old dream of landing on the moon. This was a major milestone in the new era of space exploration. We invite you to explore this interactive experience and relive the excitement of the first moon landing.

News Briefs

Learn how UD researchers are sharpening that competitive edge, fighting brain cancer, giving credit where credit is due, partners in disaster research and UD-NUVVE collaboration

Partnerships in progress

Multiple partnerships took wing in the past year to ensure UD’s scholarly efforts have the broadest and most sustained impact. Learn about the collaborations that ensure a UD world-class educational experience while serving as a major force for economic development.

Honors

Eight UD professors recently received the National Science Foundation’s highly competitive CAREER Award, which is given to scientists and engineers who exemplify the role of teacher-scholars through their outstanding research and teaching.