What’s it like to be on a ship for 4 to 6 weeks off Greenland?

How do you work and sleep with 24 hours of daylight?

Do you take your wife along on your expeditions?

I am asked these questions often when people hear about my career as an Arctic oceanographer.

Leaving Newark, Delaware, on Monday, July 30, 2012, we meet the Canadian Coast Guard Ship (CCGS) Henry Larsen four days later at Thule Air Force Base in northern Greenland. Arriving again after three years, I help the crew load the ship with the food we will eat over the next three weeks. The first meal is usually just sandwiches because the cooks arrived with us and are unpacking their gear and food the same way that we scientists try to find and unpack our tools and electronics.

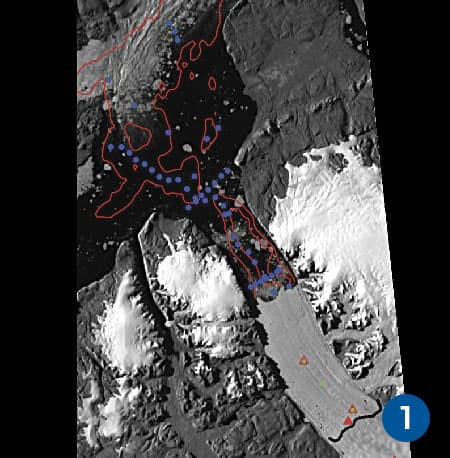

Unlike the food, most science gear was sent three months earlier when the ship was still in St. John’s, Newfoundland. When the ship pushes off the dock the next day, we sail north for two to three days to recover ocean sensors where we placed them three years earlier in 1,000 feet of water between northern Greenland and Canada’s Ellesmere Island.

We are at sea, finally. The feelings combine those of Easter egg hunting (finding boxes), Christmas Eve (unpacking boxes) and moving to a new hip neighborhood (the ship). Everyone is checking out everyone else, and new friends are made quickly.

Having helped the crew with loading the food pays unintended dividends. At night at the bar, it dawns on me that the two unknown people I was lending a helping hand earlier included the first officer and the helicopter pilot. A good start, we share stories of past adventures.

As is true of all icebreakers, the Henry Larsen is a complex community with all the functionality of a city. Capt. Wayne Duffett is in overall command. His job is to manage an airport, a fire department, a power plant, a sanitation department, a hospital, a restaurant, a hotel, a supermarket, a weather station, a port facility, a civil administration, etc. All of this is done with only 22 crew and 17 officers who work around the clock on a variety of schedules.

One way to get into trouble on Canadian icebreakers is failing to honor old traditions that date back to the Royal British Navy. It starts with breakfast. There are two places to eat: a cafeteria for the crew next to the kitchen and a dining room for officers and scientists one deck above. The six square tables seat the same people during each meal according to rank.

The captain sits at the head table with the chief engineer and the chief scientists. The first and second officers and engineers have their table while specialists such as the nurse, electronics technician, ice observer and logistics officer have theirs, and so on. Formal attire is required, which during Sunday lunch includes a jacket or dress. All meals are served by two stewards who also set tables and explain the proper use of all the silver. This is quite distinct from more egalitarian German or Swedish or American icebreakers where people mix and mingle during meal times.

Breakfast, lunch and dinner structure the day on all ships. Day and night are defined by them because the sun is always up, and time zones are arbitrary. Furthermore, sleep is dictated by the work schedule as both ship and science operate 24 hours each day. Someone always sleeps.

My favorite time to work is between midnight and breakfast when the ship is quiet, and most of the hustle and bustle of helicopters, Zodiacs, planning, meetings, organizing is over. Work usually means lowering an electronic sensor package over the side while the ship stops.

As soon as the package is back on deck with new data on how temperature and salinity varies with depth, the ship moves to the next station to again take another such profile and so on. It only requires four people to do this: the officer navigating the ship, who is assisted by a helmsman to do the steering, and me the scientist, with a helping hand.

Time passes really fast and the rhythm of stopping and going every 45 minutes or so is very soothing to me. There is time to roam the galley for coffee and snacks, there is time to visit the navigator on the bridge in person, there is time to get into deep philosophical or scientific discussion, there is even time to process and interpret the new data. By the time breakfast comes,

I share the night’s events with the next shift that just got out of bed while I turn in.

Learn more at Prof. Muenchow’s Icy Seas Blog — icyseas.org

MORE STORIES

2017 Research in Progress

What’s it like to do research in the Arctic? What ‘s it like to be on a ship for 4 to 6 weeks off Greenland? How do you work and sleep with 24 hours of daylight? Oceanographer Andreas Muenchow gives us a glimpse into his world.

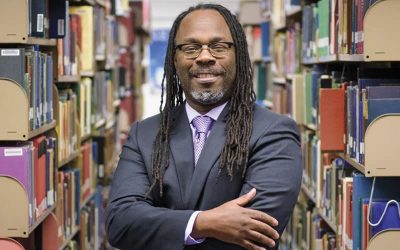

The Quiet Revolution

Trevor A. Dawes learned how libraries can change people’s lives when he was a college student. Now, he’s leading the charge to make the UD Library, Museums and Press an even greater force for good.

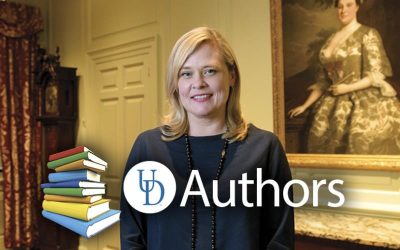

The hidden lives within a portrait

A 1746 portrait would launch a global journey into 18th-century life and present the past in a way never done before. The portrait was of Anne Shippen Willing, and what she wore would lead historian Zara Anishanslin on a journey to the far corners of the world—and launch a bold new way of looking at the past.

Filling a Real Demand for Simulated Care

Nursing instructor Amy Cowperthwait and her students are inventing products with a common goal: teaching compassionate patient care. Cowperthwait’s startup links students, engineers, business experts on quest to teach challenging medical procedures.

Suit Me Up for Mars

When astronauts make the “Journey to Mars,” NASA wants every protective measure available in place. The space agency contracted with ILC Dover to develop a new spacesuit, and ILC enlisted several materials experts at the University of Delaware to work on a suit that can handle whatever space might throw at them.

A NIIMBL Approach To Making Modern Medicines

Biopharmaceuticals have emerged recently and are having a revolutionary impact on vexing diseases such as cancer. The National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL), headquartered at the University of Delaware, is at the forefront of making medicines more accessible to Americans.

Exploring the Red Planet

NASA wants to put humans on Mars by the early 2030s. University of Delaware researchers are helping to develop spacesuits for that mammoth expedition. Yet Mars is shrouded in mystery for many of us. So what do you know about Mars? Let’s test your knowledge.

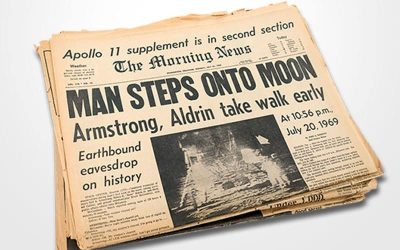

1969 – The Morning News: Man Steps onto Moon

Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong took the first moon step at 10:56 p.m., Delaware time, just six hours and 39 minutes after he and Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. fulfilled the age-old dream of landing on the moon. This was a major milestone in the new era of space exploration. We invite you to explore this interactive experience and relive the excitement of the first moon landing.

News Briefs

Learn how UD researchers are sharpening that competitive edge, fighting brain cancer, giving credit where credit is due, partners in disaster research and UD-NUVVE collaboration

Partnerships in progress

Multiple partnerships took wing in the past year to ensure UD’s scholarly efforts have the broadest and most sustained impact. Learn about the collaborations that ensure a UD world-class educational experience while serving as a major force for economic development.

Honors

Eight UD professors recently received the National Science Foundation’s highly competitive CAREER Award, which is given to scientists and engineers who exemplify the role of teacher-scholars through their outstanding research and teaching.