Historian Roger Horowitz sees many opportunities for collecting the oral histories of diverse populations, those who lived through historic events, those with specific expertise, those at all levels of society.

“Everybody has a story,” he said. “Oral histories bring students into a conversation with the past. By its nature, oral history engages the community.” Pre-pandemic photo by Evan Krape

quite possible that every day you walk past, talk over or are simply oblivious to some of the most interesting stories on our planet. That person across the street, down the hall or next to you on the couch, for example — how much do you really know about them and their experiences?

quite possible that every day you walk past, talk over or are simply oblivious to some of the most interesting stories on our planet. That person across the street, down the hall or next to you on the couch, for example — how much do you really know about them and their experiences?

If you learned the art of the interview and the craft of the oral history, you might discover you are in the company of many astonishing souls.

Long before there were text messages, property records, depositions or love letters, before there was a keyboard, printing press, quill pens or even crudely sharpened stones that could carve into the wall of a cave, people were learning about life from other people’s stories.

Thousands of years later, we still like learning things that way, says historian Roger Horowitz.

“The past is not abstract,” he said. “It’s about John, Sam, Irving, Phyllis. And that connects with the way we most want to learn about history — through their stories.”

Last fall, Horowitz taught students at the University of Delaware how to capture and curate such stories, collaborating with the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware on an oral history project that focused on senior members of the Jewish population in Wilmington, Delaware.

ABOVE: Oral History Class with (back row, left to right) Gail Pietrzyk, archivist for the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware, historian Roger Horowitz, University of Delaware students Jordan Spencer, Fiona Sia, Jacob Budd, Benjamin Glazer and (front row, left to right) Dalia Handelman, Dale Weiss, Laura Mays and Megan Heston. Pre-pandemic photo by Evan Krape.

He is a member and leader in the Oral History Association, which has an extensive network of historians and offers comprehensive information on principles and best practices of these projects.

Roger Horowitz is director of Hagley Museum’s Center for the History of Business, Technology and Society and teaches history and Jewish Studies as an adjunct professor at UD. Pre-pandemic photo by Evan Krape.

“The past is not abstract. It’s about John, Sam, Irving, Phyllis. And that connects with the way we most want to learn about history — through their stories.”

— ROGER HOROWITZ

University researchers must observe careful protocols and safeguards when dealing with human subjects, ensuring informed consent and other protections, and that can be a painstaking process at times.

“But knowing that all the i’s are dotted and the t’s are crossed and that thought is given to preparation and planning gives us a great sense of security, that it has been handled carefully,” Pietrzyk said. “I’m delighted that these interviews are being created, just delighted.”

The interviewees ranged from about 70 years old to more than 100. They had much to share about Jewish life after World War II. Some wondered why their stories were of interest or value to anyone.

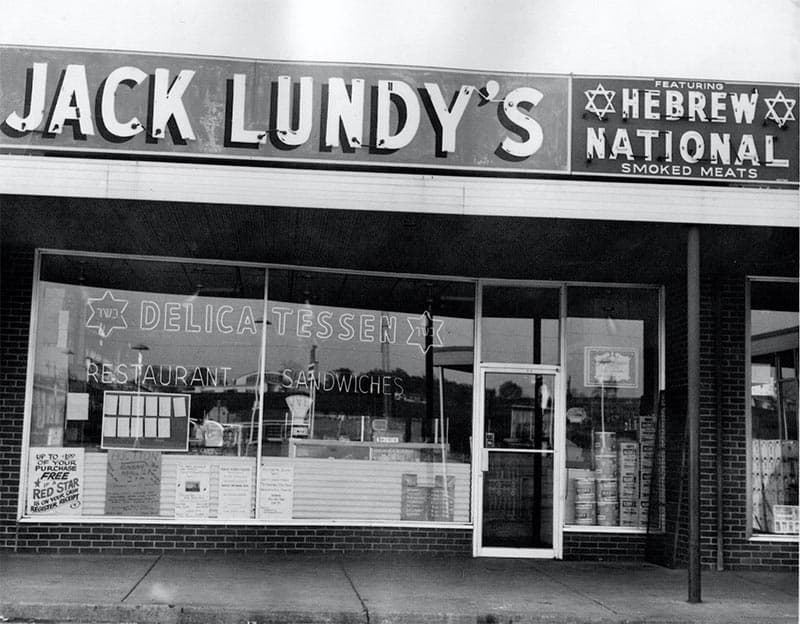

The experiences of these elders have not been the focus of much research, but they reveal context and nuanced perspectives that can inform our understanding of the past and its influence on the present. They described family and community life, Sabbath customs, experiences in business, education and encounters with anti-Semitism.

Many interviewees shared stories about the iconic tin Blue Box, known as the “pushke,” which has been used in Jewish households for more than a century. Families placed donations into that box for the Jewish National Fund, which first used the money to purchase land in Palestine and then to support the nation’s establishment.

“When they were growing up, Israel wasn’t even a nation yet,” Handelman said. “It was being established. It is 70 years old now and a thriving technology center. They knew a time when there was none of that. You can learn from anyone — and the advice they’d give is so important to listen to.”

She pointed to a powerful memory from Holocaust survivor Ann Jaffe, who said she was filled with hatred after the experience.

“Her father sat her down and asked, ‘We were victims of hatred, did you like it?’ Ann quickly responded, ‘I hated it, of course, I hated it.’ And her father said, ‘Then why would you do to others the thing that was so hateful to you?’”

Such wisdom can transform you.

“If a woman like her can let go of hatred, then we should all be able to do so as well,” Handelman said.

Handelman set the table for UD’s 2019 class by working as an intern with Horowitz in UD’s Summer Scholars program, which gives undergraduate students experience in research. During that internship, she interviewed 10 people for the project, including Faith and Lou Brown of Brandywine Hundred.

During her interview with the Browns, Dalia and Faith discovered they had a shared experience — volunteer duty with the Israeli army. Faith’s duty took place shortly after Israel’s birth as a nation in 1948 and included many subsequent trips and tasks such as assembling and cleaning Uzi machine guns. Dalia’s service came during her high-school years.

The significance of these kinds of conversations was made clear again earlier this year, when two of the people Dalia interviewed in the summer of 2019 passed away — Faith Brown’s husband, Lou, and Yetta Chaiken, a 1943 graduate of UD who provided significant support for UD’s Jewish Studies Program and was awarded the University’s Medal of Distinction in 1999.

“We are so grateful that the UD program helped us to preserve their stories and celebrate the remarkable lives recorded in all of the interviews,” Pietrzyk said.

Handelman met with students in Horowitz’s 2019 fall semester class as they learned the elements of doing oral history well. They learned how to manage logistics, the best places to conduct an interview, how to structure an interview. They planned their questions and learned how to record the interviews and write summaries of them.

Almost 20 people — with deep insight into business, education, health care, sports, faith and culture — sat for those interviews, most often recorded in their homes.

“What I valued most was the ability to have a conversation with people who have lived a long life and have made some major contributions to the world,” said Jordan Spencer, who graduated in May with a degree in history education and a minor in political science. “After interviewing them, I was able to see the power and impact of the legacy that they have created. In their story it became evident that wherever they went they positively impacted someone’s life. I can say that they have already given back to the world and have created a legacy that is everlasting.”

Spencer said he was surprised by the clarity with which many recalled events and dates. One couple he interviewed helped each other remember specifics, too.

Memories fade, of course, and sometimes stories get mixed up, exaggerated or misinterpreted. Some historians discount the value of oral histories for those reasons. Horowitz makes a strong case for them.

“Yes, memory is fallible,” he said. “And also, people often change stories to make themselves seem better or more important than they may have been so it’s regarded as a source that can be inaccurate. But all sources can be inaccurate. Many sources that are written sources are just written down oral sources, such as articles written by journalists, based on oral interviews.”

Supplementary research is always needed to verify, clarify and provide context.

ABOVE: Roger Horowitz, an adjunct faculty member in UD’s history department and an affiliated professor with the Hagley Program, geared his Fall 2019 HIST400: History Capstone Seminar class toward “Oral History and The Jewish Experience.” For this class, he partnered with the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware to have his students interview members of Delaware’s Jewish community about their life and experiences. Pre-pandemic video by Ally Quinn.

The Jewish Historical Society plans to post the UD interviews on its website and add these new materials to its considerable holdings housed at the Delaware Historical Society, where they are available to other researchers, Pietrzyk said. The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic put a halt to interviews in 2020, but Handelman continued the work this past summer, transcribing the interviews and identifying portions that would be useful for the historical society’s website.

“Roger has been really supportive and helpful and has worked with us to nurture that link with Hagley and UD,” she said. “We have talked to Roger about training other people to do oral histories. We can’t thank them enough. It’s a blessing. We’ve got some wonderful collections to share. As a historian, I know the value of going to these documents…. You read these documents and you see the real life, as it was happening, not filtered or presented.”

Many of Horowitz’s students had no previous deep understanding of the Jewish experience. But the project was special in a personal way for Handelman, who said she grew up in a thriving Jewish community.

“I learned so much from each person,” she said, “and I have seen how me caring and putting in the time talking to these people affects them. I get messages from them like: ‘You should call me. I want to know what’s up with your life!’

“And being 19, communicating with people who are 90 to 100 years old is very special. I can’t stress that enough. I wrote down quotes that I never want to forget — and they don’t even realize it. I have left some interviews almost crying.”

History has enormous power when brought to the personal, relational level. And it always holds surprises. Horowitz experienced that during a series of interviews — 20 hours in all — he did with his stepfather, Al Johnson, to explore his stepfather’s military service in World War II, Korea and Vietnam.

“Tell me about your first memory,” Horowitz suggested, to get things going.

“It was the day my parents left me,” his stepfather replied. He then related a complex story of family history Horowitz had never heard before. A month later, Al Johnson died of asbestosis.

So don’t wait. Make that appointment. Write down some questions. Listen well. Take careful notes. Get to know someone — for their sake, for yours, for all of us.

Much history was shared during the oral history interviews, including stories about:

- Keeping carp in the bathtub in order to make gefilte (stuffed) fish for Sabbath or Passover meals

- TV test patterns that filled screens before 24-hour broadcasting was the standard

- Party-line telephones

- Having to cross the Delaware River by ferry because the bridges did not yet exist

- Going to racially segregated schools, then going to community dances with Black students

- Red-lined areas where Jewish families could not purchase homes

- Rules and regrets about intermarriage between Jews and non-Jews

- Traditions brought from Russia and Ukraine

- Patriarchal customs

- The desire to assimilate into American life and the loss of some traditions

- How one interviewee established dental care for indigent students in the Christina School District

- Drifting from the faith and returning to it after a death in the family

- Encounters with anti-Semitism, overt and subtle

- The pride of Jewish heritage

- One fraternity, one sorority that Jewish students could join at UD

- The challenges of keeping a kosher house

- Attending Hebrew school five days each week

- Restricted roles of women at the synagogue

- Collecting money to support the creation of the Israeli nation

- Being the only Jewish man on a U.S. military base in Morocco

- Growing up as a Jew in Memphis, Tennessee

- House calls by doctors that cost $2 per visit

- Playing phonograph records with Hebrew and Yiddish folk songs on the Victrola

- Purchasing a new home for $7,000, paying $20 a month for rent, 12 cents a gallon for gas

- Spending 21 days seasick on a Turkish steamer to get to Israel in 1949

- Israeli music festivals and dance groups

MORE STORIES

From the Vice President for Research, Scholarship and Innovation: Moving Forward

The UD research community continues to navigate COVID-19, with health and safety the highest priority. In spite of hardships, we’re facing the pandemic with vigilance and resilience.

News Briefs

Check out our COVID-19 research, a virtual visit with the editor-in-chief of Science, and undergrads at work on the Frontiers of Discovery.

Honors: Celebrating Excellence

UD faculty and students have won major recognition for their expertise and contributions.

Guess Who’s Powering Up UD’s Research Engine?

This issue of the University of Delaware Research magazine introduces you to a critical creative force at UD — our graduate students and postdoctoral researchers. Their ingenuity is lighting new routes to discovery and solutions.

Front Edge of Discovery: Strengthening democracy for a better world

It all began with a Joseph Conrad novel. Doctoral student Pablo McConnie-Saad discusses his journey to better understand democracy, as the first Whittington Graduate Fellow at the Biden Institute.

Front Edge of Discovery: Developing resilient Black girls

Doctoral student and Graduate Scholar Nefetaria Yates is examining school discipline and the tactics Black girls have developed for dealing with the pressures they face. Her ultimate goal is to elevate voices that have been silenced.

Front Edge of Discovery: Helping children move

Entrepreneur Ahad Behboodi wants to see kids with cerebral palsy move more freely. He plans to commercialize a robotic foot device with the power to help them.

Front Edge of Discovery: A clinical science approach

Lexie Tabachnick, in her fifth year of doctoral studies, helps to mentor other grad students and undergraduates while she studies the powerful impact a UD-developed family intervention program is having on vulnerable kids.

Front Edge of Discovery: Beyond the hands of a potter

Sanchita Balachandran, associate director of Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum and doctoral student in preservation studies at UD, is uncovering the forgotten makers of ancient Greek ceramics, and in so doing, changing our understanding of the past.

Front Edge of Discovery: Changing the world, one food waste at a time

Elvis Ebikade thinks potato peels hold a lot of promise. He’s working on converting the food waste to valuable chemicals and fuels that can power an environmentally-friendly future.

Front Edge of Discovery: The thing about permafrost is…

As a postdoctoral researcher, Liz Coward collected samples of permafrost from the icy walls of a research tunnel in Alaska to study the carbon stored within it.

A Robotics Revolution

Researchers at the University of Delaware are leveraging robotic systems to gain traction on tough problems. Learn how they are driving forward transformative solutions in agriculture, precision medicine, health care, cybersecurity, marine ecology and more.

UD Robotics: Antarctic food webs

University of Delaware researchers Matthew Oliver and Katherine Hudson think that some biological hotspots in Antarctica may operate less like local farms and more like grocery stores. If they are correct, it could provide new information about how this ecosystem will be affected under climate change.

UD Robotics: Robots these days!

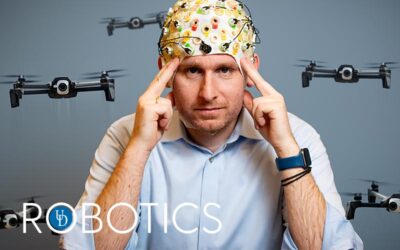

Brain-swarm technology is meant to connect minds and machines. For Associate Professor Panos Artemiadis such robotics research has one purpose: To make life and work better for humans.

UD Robotics: Meet me on the cutting edge

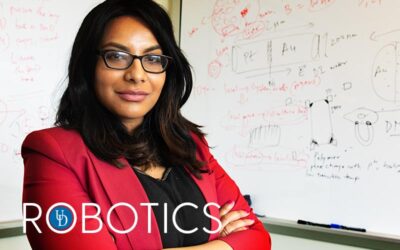

Sambeeta Das is forging into an exciting world you can see only with high-powered microscopes, where sci-fi meets reality. Welcome to the world of microrobots!

UD Robotics: Allies in Overcoming Stroke

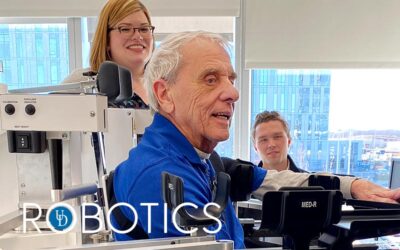

Stroke is a leading cause of long-term disability, but UD Professor Jennifer Semrau is working to change that. With the help of a robot, she’s uncovering a critical sixth sense that gets sidelined with stroke.

UD Robotics: Startup with Roots

Adam Stager is working on chemical-free ways to help strawberry farmers improve yield using an autonomous field robot.

UD Robotics: Social Robots

Children have grown up with interactive technologies like Siri, Google and Alexa, but they don’t always know how to stay safe online. UD researchers are working on ways to help them.