Environmental

GRAD STUDENTS ON THE FRONT EDGE OF DISCOVERY

Liz Coward, a postdoctoral researcher in environmental chemistry at the University of Delaware, has seen firsthand the sobering impact climate change is having on permafrost in its natural environment. Working in the lab of Donald Sparks, Unidel S. Hallock du Pont Professor of Plant and Soil Sciences and director of the Delaware Environmental Institute, she has studied core samples of permafrost collected from Alaska, among other things.

Pre-pandemic photo by Kathy Atkinson

Environmental

GRAD STUDENTS ON THE FRONT EDGE OF DISCOVERY

Liz Coward a postdoctoral researcher in environmental chemistry at the University of Delaware, has seen firsthand the sobering impact climate change is having on permafrost in its natural environment. Coward works in the lab of Donald Sparks, Unidel S. Hallock du Pont professor of plant and soil sciences and director of the Delaware Environmental Institute, where she is studying core samples of permafrost collected from Alaska, among other things.

The thing about permafrost is …

by Beth Miller

The thing about permafrost is right there in its name. It’s supposed to be permanently frozen. Otherwise it would be called tempofrost.

Now, sad to say, a name change may be in order. The frozen tundra is melting in certain parts of our planet. It’s not a matter of if or when. It’s melting now.

Liz Coward, who worked as a postdoctoral researcher in environmental chemistry at the University of Delaware, has seen firsthand the sobering impact climate change is having on permafrost in its natural environment. Coward worked in the lab of Donald Sparks, Unidel S. Hallock du Pont Professor of Plant and Soil Sciences and director of the Delaware Environmental Institute, where she studied core samples of permafrost collected from Alaska, among other things.

Many researchers are looking at what will be released as the melt continues and how that will affect the planet. At the 2019 American Geophysical Union Conference in San Francisco, for example, more than 300 abstracts were presented on permafrost studies, Coward said.

Her research focused instead on the persistence of carbon, how it is stabilized and kept in place. Permafrost was considered a virtual vault for anything captured within it, including carbon.

“Until it’s not,” she said.

The layer of material above permafrost that thaws seasonally, known as the active layer, is deepening. As permafrost thaws, things are changing there, mixing. Microbes are becoming active.

“Is there anything that will keep the carbon stabilized and render it not bioavailable?” she said.

That’s what she has studied in Sparks’ lab. One of the things anyway.

Examining delicate materials such as permafrost requires special handling, something Liz Coward achieved by using the “glove box” which keeps materials in a protected environment. Pre-pandemic photo by Kathy Atkinson

She came to UD on a “cold call,” she said. After studying biology at Haverford College and earning her doctorate in earth science at the University of Pennsylvania, she emailed Sparks to apply for a postdoc position in his lab. She pitched a variety of projects she might work on to see if any would interest him.

“Let’s just do all of those,” he told her.

Well, then — yes indeed!

“The cool thing about the environment is you can really ask lots of different types of questions,” she said. “You can look at ecosystem-scale questions and you can look at nanoscale questions.”

Permafrost wasn’t one of her pitches. That project emerged from a new research partnership UD joined a few years ago, stemming from Josh LeMonte, who earned his doctorate at UD and now works for the U.S. Army’s Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC). The Sparks laboratory collaborates with ERDC’s Permafrost Tunnel Research Facility in Fox, Alaska, a unique laboratory environment carved into the permafrost there.

Coward visited the permafrost tunnel — operated by the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) — with recent UD doctoral graduate Tyler Sowers. They returned with two giant coolers full of core samples, drawn from the 15-meter-thick permafrost, some of which is 30,000 years old. There are fascinating things — including mammoth tusks — embedded in those icy walls, she said.

Coward worked with those core samples now in Sparks’ lab at the Patrick T. Harker Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering (ISE) Lab.

What is permafrost made of?

Permafrost is made of a combination of soil, rocks and sand, held together by ice. The soil and ice in permafrost stay frozen all year long.

Near the surface, permafrost soils also contain large quantities of organic carbon — the remains of dead plants that didn’t decompose or rot away because of the cold. Lower permafrost layers contain soils made mostly of minerals.

A layer of soil on top of permafrost does not stay frozen all year. This layer, called the active layer, thaws during the warm summer months and freezes again in the fall. In colder regions, the ground rarely thaws — even in the summer. There, the active layer is very thin — only 4 to 6 inches. In warmer permafrost regions, the active layer can be several meters thick.

Permafrost Tunnel Research Facility

The U.S. Army’s Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC) Permafrost Tunnel Research Facility in Fox, Alaska, is a unique laboratory environment carved into the permafrost there. This tunnel, originally established in the 1960s, was used to evaluate underground permafrost excavation techniques. It was during the excavation process that the tunnel’s usefulness as a natural laboratory became clear. The tunnel’s frozen walls expose a continuous cross section of undisturbed, perennially frozen, fossil-rich silt, sand and gravel on top of bedrock. The Permafrost Tunnel’s syngenetic permafrost has captured climate information from the last 40,000 years. Some of this information allows an understanding of the approximate duration and severity of the cold period, while other information indicates that warming periods existed at times. Today the Permafrost Tunnel is an active underground laboratory available for a variety of research programs. Each year, it welcomes many research scientists and engineers interested in the processes and properties of frozen soils.

Rucha Wani, an undergraduate majoring in marine science, said Coward’s advice and mentorship helped her grow as a young scientist. Photo by Elizabeth Coward.

Rucha Wani, an undergraduate majoring in marine science, said Coward’s advice and mentorship helped her grow as a young scientist. Photo by Elizabeth Coward.“Postdocs are supposed to be the hammers — specialized tools that do one thing and do it super well,” she said.

Along the way, she also mentored graduate and undergraduate students, including fellows of the Delaware Environmental Institute (DENIN), helping them develop their own projects, questions and experiments, and gain experience in what it takes to do good research.

“It’s good for us to sit with that tedious part,” Coward said. “That’s the way science really works — what are the best questions to ask and how do you go about answering those questions in the best way possible?”

Among the students she worked with was undergraduate Rucha Wani, who is majoring in marine science.

“She has always encouraged me to take a very active role in the research process, from the ideation of the project all the way to the analysis of the results,” Wani said in an email. “She’s helped me prepare for graduate school and I think she’s given me a lot of unique opportunities as an undergraduate student, especially by giving me the tools to execute a good research project…. Her advice and mentorship have really shaped my growth as a young scientist and I am very grateful for that.”

Coward grew up in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she spent a lot of time outdoors, wondering about how the environment works. Research emerged as a fascinating option for the future during her undergrad years at Haverford College. Her adviser there, chemist Helen White, was studying samples from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. Assisting with that work prompted Coward to get serious about research.

She hopes to see more women and more people of color do the same.

“At the university scale, getting students into research experiences is key,” she said. “If the lab excites you, it can sustain you through classes you may not like.”

Research is always a challenging path, yes, but Coward says the workload of a postdoc is a bit lighter than that of a graduate student and/or a doctoral student.

“I think being a postdoc is the best of a lot of worlds, especially if you have a great P.I. [principal investigator] like Don Sparks. For the most part, I have been able to work on projects I’m interested in.”

She and her husband, an emergency medicine fellow, moved to San Diego this past summer, where she is exploring similar questions, focusing on carbon cycling in marine systems, at the University of California, San Diego and Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

— Liz Coward

Donald Sparks is a researcher, teacher, mentor and director of the Delaware Environmental Institute (DENIN), a leading center for science, engineering and policy at the University of Delaware. He was the 2015 medalist for the Geochemistry Division of the American Chemical Society, the first soil scientist to receive that prestigious award.

Get to know our grad students

This special section of our digital magazine highlights a powerful force behind UD’s research engine.

MORE STORIES

From the Vice President for Research, Scholarship and Innovation: Moving Forward

The UD research community continues to navigate COVID-19, with health and safety the highest priority. In spite of hardships, we’re facing the pandemic with vigilance and resilience.

News Briefs

Check out our COVID-19 research, a virtual visit with the editor-in-chief of Science, and undergrads at work on the Frontiers of Discovery.

Honors: Celebrating Excellence

UD faculty and students have won major recognition for their expertise and contributions.

Guess Who’s Powering Up UD’s Research Engine?

This issue of the University of Delaware Research magazine introduces you to a critical creative force at UD — our graduate students and postdoctoral researchers. Their ingenuity is lighting new routes to discovery and solutions.

Front Edge of Discovery: Strengthening democracy for a better world

It all began with a Joseph Conrad novel. Doctoral student Pablo McConnie-Saad discusses his journey to better understand democracy, as the first Whittington Graduate Fellow at the Biden Institute.

Front Edge of Discovery: Developing resilient Black girls

Doctoral student and Graduate Scholar Nefetaria Yates is examining school discipline and the tactics Black girls have developed for dealing with the pressures they face. Her ultimate goal is to elevate voices that have been silenced.

Front Edge of Discovery: Helping children move

Entrepreneur Ahad Behboodi wants to see kids with cerebral palsy move more freely. He plans to commercialize a robotic foot device with the power to help them.

Front Edge of Discovery: A clinical science approach

Lexie Tabachnick, in her fifth year of doctoral studies, helps to mentor other grad students and undergraduates while she studies the powerful impact a UD-developed family intervention program is having on vulnerable kids.

Front Edge of Discovery: Beyond the hands of a potter

Sanchita Balachandran, associate director of Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum and doctoral student in preservation studies at UD, is uncovering the forgotten makers of ancient Greek ceramics, and in so doing, changing our understanding of the past.

Front Edge of Discovery: Changing the world, one food waste at a time

Elvis Ebikade thinks potato peels hold a lot of promise. He’s working on converting the food waste to valuable chemicals and fuels that can power an environmentally-friendly future.

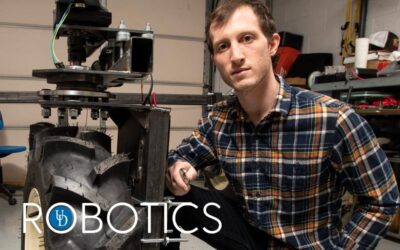

A Robotics Revolution

Researchers at the University of Delaware are leveraging robotic systems to gain traction on tough problems. Learn how they are driving forward transformative solutions in agriculture, precision medicine, health care, cybersecurity, marine ecology and more.

UD Robotics: Antarctic food webs

University of Delaware researchers Matthew Oliver and Katherine Hudson think that some biological hotspots in Antarctica may operate less like local farms and more like grocery stores. If they are correct, it could provide new information about how this ecosystem will be affected under climate change.

UD Robotics: Robots these days!

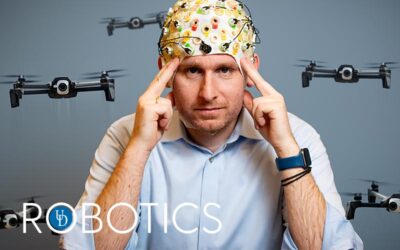

Brain-swarm technology is meant to connect minds and machines. For Associate Professor Panos Artemiadis such robotics research has one purpose: To make life and work better for humans.

UD Robotics: Meet me on the cutting edge

Sambeeta Das is forging into an exciting world you can see only with high-powered microscopes, where sci-fi meets reality. Welcome to the world of microrobots!

UD Robotics: Allies in Overcoming Stroke

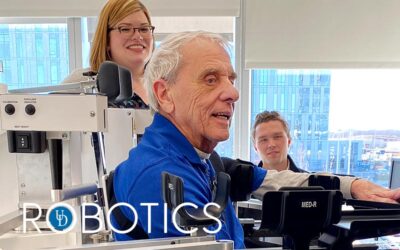

Stroke is a leading cause of long-term disability, but UD Professor Jennifer Semrau is working to change that. With the help of a robot, she’s uncovering a critical sixth sense that gets sidelined with stroke.

UD Robotics: Startup with Roots

Adam Stager is working on chemical-free ways to help strawberry farmers improve yield using an autonomous field robot.

UD Robotics: Social Robots

Children have grown up with interactive technologies like Siri, Google and Alexa, but they don’t always know how to stay safe online. UD researchers are working on ways to help them.

A Jewish Oral History

A class helps preserve the precious stories of a little-documented time in Jewish life.

Test Your Knowledge: Getting Back to Nature

To reduce stress and strengthen our immune systems, experts often point us to the outdoors. So let’s get moving! There’s lots to see and hear, absorb and appreciate in nature.