Preservation studies

GRAD STUDENTS ON THE

FRONT EDGE OF DISCOVERY

Sanchita Balachandranis associate director of the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum and a doctoral student in preservation studies at the University of Delaware. Her research is inspired by questions that arise when you see an object from ages ago. How in the world did they make that? And who made it? Using technology, she’s uncovering hidden clues in ancient Greek ceramics, bringing once-invisible artisans to life and changing our understanding of the past.

Pre-pandemic photo by James T. VanRensselaer

Preservation studies

GRAD STUDENTS ON THE FRONT EDGE OF DISCOVERY

Sanchita Balachandra is associate director of the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum and a doctoral student in preservation studies at UD. Her research is inspired by questions that arise when you see an object from ages ago. How in the world did they make that? And who made it? Using technology, she’s uncovering hidden clues in ancient Greek ceramics, bringing once-invisible artisans to life and changing our understanding of the past.

Beyond the hands of a potter:

Uncovering hidden identities

by Tracey Bryant

S he rises early in the morning and goes to bed very late at night. Sanchita Balachandran said the long days were actually one of the joys of going back to graduate school a few years ago, while raising a family she adores and working full-time at her dream job as associate director of the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum. Trying to do it all now, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, seems impossible at times.

“Trying to navigate work/life and the kids’ online/hybrid learning is, well, chaotic,” she said in early November 2020. Nevertheless, she is driven to continue her studies.

“I’m inspired by the professors and excited about the materials I’m studying every day,” she said. “It’s really exhilarating.”

Balachandran already has two graduate degrees — in art history and art conservation — from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. But a few years ago, after a project with her students generated more questions than answers, she gave in to the relentless desire to know more and applied to the Ph.D. program in preservation studies at the University of Delaware.

Rather than a discipline-based course of graduate study, UD’s program combines cross-field expertise, integrating ideas and methods from a full range of preservation-related disciplines — in Balachandran’s case that includes archaeology, art history, history, chemistry and materials science, pottery-making, cognitive science and drawing pedagogy.

“I work with very technical things to very traditional historical texts, and I kind of need everything to explore the questions I’m interested in,” said Balachandran, who also is a senior lecturer in the Department of Near Eastern Studies at Johns Hopkins. “That’s what really drew me to UD’s program.”

ABOVE: This elegant kylix (pronounced “kye-lix”), or cup, was made in Athens around 510 BCE. Courtesy of Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum. Photo by James T. VanRensselaer

ABOVE: This elegant kylix (pronounced “kye-lix”), or cup, was made in Athens around 510 BCE. Courtesy of Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum. Photo by James T. VanRensselaerThe inspiration of a familiar question

Balachandran’s doctoral research originally was inspired by a question that comes to mind when you see or hold an object from the past: How in the world did they make that? As her work has evolved, she now asks: What can we know of the person who made the object through only what they left behind?

Exploring such questions took hold in a big way in 2015, when she and 13 undergraduate students set out to re-create one of the most iconic and elegant objects from ancient Greece — the kylix (pronounced “kye-lix”), or cup. These wide-bowled drinking vessels with their distinctive handles were made some 2,500 years ago for men to use at male drinking parties called “symposia.”

The focus of the class was a striking kylix made in Athens around 510 BCE. In Baltimore since 1887, it normally sits in a display case that Balachandran walks by every day at work. Painted a lustrous black, the kylix has a scene in deep red in the center circle, or tondo. The decoration shows a young man in a pottery shop purchasing what may have been his first cup. Tiny brush strokes detail the “peach fuzz” on his face. The vessel is surprisingly lightweight and has a smooth, silken surface. It even bears the signature of the painter, Phintias.

Balachandran said she wanted to have her students, as well as herself, “apprentice themselves” to the unknown ancient potter who made this vessel. And so, in collaboration with expert potter Matthew Hyleck, from Baltimore Clayworks, they began consulting with other specialists, including art historians, archaeologists, and experts in ancient Greek literature, to try to reproduce the ancient process.

ABOVE: Sanchita Balachandran (center) works with Camilla Ascher and Matthew Hyleck on the firing chamber for their replica ancient Greek kiln in Baltimore Clayworks studios in January 2015. Photo by James T. VanRensselaer. Courtesy of Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum

Besides gaining an immense appreciation for the ancient artisans, the students asked numerous questions: How did the artisans stack the cups in the kiln for firing? (Location has a lot do with the success of the dark lustrous color.) What did they use to paint such detailed features? (Horse hairs, hog hairs and even cat whiskers were tested.) What did it taste like to drink from the cup? (It has a mineral taste.)

The class made about 10 pots, and scores more materialized over the next year as part of a research project funded by Johns Hopkins. They documented their trial and error through writing, photography and film.

“We made more than 200 pots — many of them are still in my office,” Balachandran said.

Photo by Angela Elliott, courtesy of Walters Art Museum.

“I’m interested in how thinking about the diversity of these ancient makers and their lived experiences offer us ways to think about the dignity of work, the importance of this kind of ‘essential labor,’ the need to respond to valid critiques of Classics in general at a time when it has been rightly called out for enabling white supremacy by not emphasizing the diversity of the ancient past.

I want to find ways to make sure that this research speaks to the most human of questions: Do I matter? What is my place in the world? Will anyone remember me?”

— Sanchita Balachandran

ABOVE: This detail from a drinking cup, or kylix, shows a young man, money purse in hand and leaning on a walking stick, inspecting a pottery display probably to procure drinking vessels for a symposium — a wine-drinking party for men in ancient Greece some 2,500 years ago. Note the “peach fuzz” the artist has painted on an otherwise smooth cheek. Courtesy of Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum

Bringing ancient artisans to life

Although the project opened a new window into an ancient world, Balachandran said it did not produce the level of “knowing” that she believes the fields of conservation, classics, art history and history should take up in a deeper way.

So that is now her charge. While many surviving ancient ceramics bear the fingerprints of their makers, very few are signed. In her doctoral research at UD, Balachandran hopes to uncover the identities of these producers of ceramics in ancient Athens in the 6th to 4th centuries BCE — the immigrants, the migrants, the women entrepreneurs and the people who were enslaved.

“The ancient elite had little documented interest in these artisans as people,” she said, explaining that in the few ancient texts that even mention artisans, there’s a recognition that their work is necessary, but that they are seen as a separate class because of their bodily labor.

Her detective work draws on a variety of techniques. Reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) is revealing small details never seen before — the faintest of sketches underneath paintbrush lines on pottery.

When she applied RTI to a fragment of a vessel attributed to Brygos Painter, who was active from about 490 to 470 B.C., we can see how he sketched at least three different hand positions for the figure of a youth holding a cord. And there is so much more to discover just under the surface.

Using new techniques and a fresh viewpoint, Balachandran is challenging long-accepted theories and expanding our understanding of these ancient artisans “beyond their hands,” and into real people with extraordinary expertise.

— Sanchita Balachandran

She said she especially thanks her UD advisers for their boosts right when needed, including from her adviser, renowned conservation expert Joyce Hill Stoner, associate dean for the humanities Lauren Hackworth Petersen, who is an art historian of the ancient classical world, Annette Giesecke, Elias Ahuja Professor of Classics, and conservation scientist Rosie Grayburn, who is exploring how her scientific approaches can respond to the humanistic questions Balachandran is now asking.

“I’m interested in how thinking about the diversity of these ancient makers and their lived experiences offer us ways to think about the dignity of work, the importance of this kind of ‘essential labor,’ the need to respond to valid critiques of Classics in general at a time when it has been rightly called out for enabling white supremacy by not emphasizing the diversity of the ancient past,” she said.

“I want to find ways to make sure that this research speaks to the most human of questions: Do I matter? What is my place in the world? Will anyone remember me?”

Joyce Hill Stoner is the Edward F. and Elizabeth Goodman Rosenberg Professor in Material Culture and director of UD’s Preservation Studies Doctoral Program, which mandates an interdisciplinary approach within the humanities and the sciences. It builds on unique and distinguished programs at the University of Delaware. In addition to Sanchita Balachandran’s work on ancient Greek ceramics, other topics being researched by current PSP students include the techniques of Color Field painter Morris Louis, the preservation of religious architecture in Southwest China, historical graffiti in American buildings, traditional Kurdish textiles, reexamining historically designated buildings and landscapes, and craquelure in Chinese guqin musical instruments.

Get to know our grad students

This special section of our digital magazine highlights a powerful force behind UD’s research engine.

MORE STORIES

From the Vice President for Research, Scholarship and Innovation: Moving Forward

The UD research community continues to navigate COVID-19, with health and safety the highest priority. In spite of hardships, we’re facing the pandemic with vigilance and resilience.

News Briefs

Check out our COVID-19 research, a virtual visit with the editor-in-chief of Science, and undergrads at work on the Frontiers of Discovery.

Honors: Celebrating Excellence

UD faculty and students have won major recognition for their expertise and contributions.

Guess Who’s Powering Up UD’s Research Engine?

This issue of the University of Delaware Research magazine introduces you to a critical creative force at UD — our graduate students and postdoctoral researchers. Their ingenuity is lighting new routes to discovery and solutions.

Front Edge of Discovery: Strengthening democracy for a better world

It all began with a Joseph Conrad novel. Doctoral student Pablo McConnie-Saad discusses his journey to better understand democracy, as the first Whittington Graduate Fellow at the Biden Institute.

Front Edge of Discovery: Developing resilient Black girls

Doctoral student and Graduate Scholar Nefetaria Yates is examining school discipline and the tactics Black girls have developed for dealing with the pressures they face. Her ultimate goal is to elevate voices that have been silenced.

Front Edge of Discovery: Helping children move

Entrepreneur Ahad Behboodi wants to see kids with cerebral palsy move more freely. He plans to commercialize a robotic foot device with the power to help them.

Front Edge of Discovery: A clinical science approach

Lexie Tabachnick, in her fifth year of doctoral studies, helps to mentor other grad students and undergraduates while she studies the powerful impact a UD-developed family intervention program is having on vulnerable kids.

Front Edge of Discovery: Changing the world, one food waste at a time

Elvis Ebikade thinks potato peels hold a lot of promise. He’s working on converting the food waste to valuable chemicals and fuels that can power an environmentally-friendly future.

Front Edge of Discovery: The thing about permafrost is…

As a postdoctoral researcher, Liz Coward collected samples of permafrost from the icy walls of a research tunnel in Alaska to study the carbon stored within it.

A Robotics Revolution

Researchers at the University of Delaware are leveraging robotic systems to gain traction on tough problems. Learn how they are driving forward transformative solutions in agriculture, precision medicine, health care, cybersecurity, marine ecology and more.

UD Robotics: Antarctic food webs

University of Delaware researchers Matthew Oliver and Katherine Hudson think that some biological hotspots in Antarctica may operate less like local farms and more like grocery stores. If they are correct, it could provide new information about how this ecosystem will be affected under climate change.

UD Robotics: Robots these days!

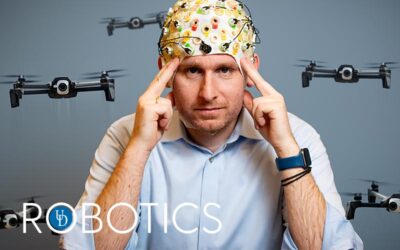

Brain-swarm technology is meant to connect minds and machines. For Associate Professor Panos Artemiadis such robotics research has one purpose: To make life and work better for humans.

UD Robotics: Meet me on the cutting edge

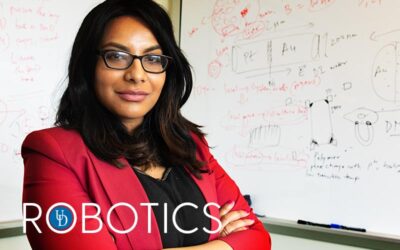

Sambeeta Das is forging into an exciting world you can see only with high-powered microscopes, where sci-fi meets reality. Welcome to the world of microrobots!

UD Robotics: Allies in Overcoming Stroke

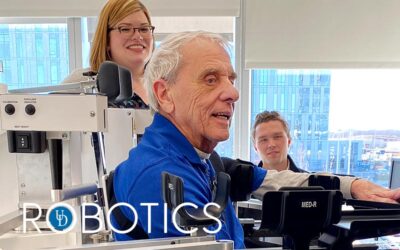

Stroke is a leading cause of long-term disability, but UD Professor Jennifer Semrau is working to change that. With the help of a robot, she’s uncovering a critical sixth sense that gets sidelined with stroke.

UD Robotics: Startup with Roots

Adam Stager is working on chemical-free ways to help strawberry farmers improve yield using an autonomous field robot.

UD Robotics: Social Robots

Children have grown up with interactive technologies like Siri, Google and Alexa, but they don’t always know how to stay safe online. UD researchers are working on ways to help them.

A Jewish Oral History

A class helps preserve the precious stories of a little-documented time in Jewish life.

Test Your Knowledge: Getting Back to Nature

To reduce stress and strengthen our immune systems, experts often point us to the outdoors. So let’s get moving! There’s lots to see and hear, absorb and appreciate in nature.