DISRUPTORS

HARNESSING BENEFICIAL MICROBES

Last November, empty store shelves greeted shoppers across 11 states searching for romaine lettuce to complement their Thanksgiving menu. The culprit: pathogenic E. coli contamination, which caused a recall by the Centers for Disease Control. One in six Americans become sick from contaminated food annually, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

UD researchers are teaming up to harness beneficial microbes to fight the tiny toxic trespassers taking aim at our food supply, as well as to boost crop production for a growing global population.

GETTING TO THE ROOT OF THE PROBLEM

So, what do a virologist, botanist and soil physicist have in common? This team from UD’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources is leveraging their collective expertise to ensure that our food supply is safe and abundant, now and in the future.

Harsh Bais

Kali Kniel

Yan Jin

Question:

What do you study, and what led you into this field?

Answer:

My lab works on plant-microbe interactions, specifically looking at how plants associate with beneficial microbes. We use both molecular and physiological tools to tease beneficial microbe-plant interactions. Our work showed that plant roots actively recruit beneficial microbes below-ground. The causes and consequences of this association is evaluated for plant growth and fitness.

My basic degree is in biochemical engineering and biotechnology, I was always fascinated by how plants react to the environment. In last 100 years of plant research, very few beneficial microbe plant associations have been characterized. We all have known and learnt about how plants are associated with rhizobium for nitrogen fixation. On the contrary, only 2-3% of land plants are adapted to the association with rhizobium species. The knowledge pertaining to how majority of land plants shape belowground microbial population is not known. The question that remains to be answered is, are plants shaping microbiome or are microbes shaping the vegetation? Answering these questions may help understand how we could grow our plants better for sustainable agriculture.

Question:

Did you color outside the lines as a kid?

Answer:

Yes, I did. My father was very good in drawing as he was a trained mechanical and automation engineer. I learnt free drawing skills from him.

Question:

Can you recount the tipping point—the idea that produced your ‘aha!’ moment?

Answer:

Since my move to UD in 2005, we had couple of interesting moments that changed our understanding about how plants respond to environment.

Finding how an injured plant associates with a beneficial-bacteria for protection, led to the discovery of an important bacterial isolate that is now a commercial product for various agricultural applications. The finding was led by a postdoc and was really critical in our understanding of how microbes help plants.

My first graduate student Dr. Meredith Biedrzycki was one of the first ones to show how plants have altruistic life style, she showed that plants are smart to differentiate between kin and strangers. To show that plants can identify and perceive root-derived signals from kin vs strangers, Meredith set up a time-lapse camera to look at root growth, when she told that root allocation was minimal in kins vs strangers, that certainly was a cool moment.

Question:

Were there many naysayers and how did you navigate that?

Answer:

There were lots of non-believers for the work we did showing that plants recognize their kin. It is always hard to show things that are different from the norm. We had to provide more convincing mechanistic facts that plants can differentiate between kin and non-kin. After our discovery, now there are numerous reports of kin recognition in plants.

Question:

Did anyone in particular inspire you to think differently?

Answer:

One scientist who has inspired me immensely is Dr. MS Swaminathan, he was considered a pioneer of green revolution in India. One thing that he said that stuck with me, is “If conservation of natural resources goes wrong, nothing will go right”. His thought process that “if agriculture fails everything fails” holds good in today’s environment when we have to boost our agricultural yield yet again to address food security issue for the growing population.

Question:

What has been most satisfying about your work? Most terrifying?

Answer:

The most satisfying part of our research was to take the basic fundamental concept of using beneficial microbe to increase crop yield from a wet lab bench to field. Our work since last decade has shown that using benign microbes as alterative agents to increase plant growth and fitness. This work has been very rewarding in terms of taking a fundamental approach to fruition to make agricultural products for conventional agriculture.

The concept that all benign microbes are good for plants is wrong, we learnt this hard way (not a terrifying moment), a PhD student in the lab discovered that not all microbes are helpful for plants and this is primarily because they don’t like other microbes in soil. Its race to acquire the best real-estate in soil and microbes compete with each other to find the best spot on plants.

Question:

What is your favorite problem at the moment?

Answer:

We work with plant-beneficial microbe interactions, to pick up the favorite problem would be showing a bias. At this juncture, the question that needs some addressing is to figure out, if plants shape belowground-microbiome or is it the microbes that are shaping the above-ground plant biomass and diversity. Our work has addressed some of the issues related to the big problem, and we are using cross-disciplinary approaches to answer some of these questions.

Question:

Does your disruptive side prove challenging at home?

Answer:

It does at times, when I try to imply some of these crazy learning approaches to my kids. I usually get an answer that you are just a “botanist” what would you know about the rest of the world. I tell my kids or whenever I get a chance to talk to young kids that they need to decide what they want to do but if you pick up a thing go all the way to find answers.

Question:

Why do you want to keep doing this work?

Answer:

I think life and culture in academia is the most satisfying one, as it gives you freedom to test multiple interesting research questions. I often say that teaching and research are like vascular bundles (tissues that transport water and sugar in plants), they are supposed to transport knowledge and it doesn’t have to be unidirectional.

The thing that keeps me going is the company of young minds, the students. Students are the most fascinating and rewarding part of life in academia. Students challenge you to be better communicators and scientists.

Question:

What do you study, and what led you into this field?

Answer:

I study diverse aspects of microbial food safety. I wanted to work in an area where applied and basic scientific contributions impact public health. What I love about this field is that our research (including that of undergraduate and graduate students) can inform both regulatory policy and the food safety policies used by the food industry.

Question:

Did you color outside the lines as a kid?

Answer:

According to my mom, I did not actually color outside or inside any lines, but preferred to draw and create my own pictures.

Question:

Can you recount the tipping point—the idea that produced your ‘aha!’ moment?

Answer:

I recall first realizing the potential impact from the data that I was observing on petri plates and on plants. I was so surprised! I was in the laboratory talking to a graduate student, who was just as surprised by the data. And the data we continue to generate continues to surprise me. It is very exciting.

Question:

Were there many naysayers and how did you navigate that?

Answer:

I think there are several people who are e comfortable with more “traditional” experiments. When people hear something original it takes a few times of hearing it before they understand it enough even to ask questions. I just keep explaining it. This is actually an awesome opportunity for students to explain a unique part of science.

Question:

Did anyone in particular inspire you to think differently?

Answer:

I have always been inspired by scientists who are not afraid to think “outside the box” and perhaps even challenge biological dogma if it is an area that is not well understood. Epidemiologists and public health officials do this often, too. Bacterial pathogens consistently challenge our thinking as new foods become involved in outbreaks that were not previously considered high-risk foods or foods at risk for contamination by that pathogen.

Question:

What has been most satisfying about your work? Most terrifying?

Answer:

It is terrifying thinking that this work is so “unusual” that it may not receive the funding needed to complete a study. Sometimes reviewers are afraid to fund a project that they have never heard of before.

The most satisfying is being able to offer a unique means to reduce the risk of contamination when we need every way that we can to reduce the risks associated with potential contamination of leafy greens.

Question:

What is your favorite problem at the moment?

Answer:

My favorite problem is assessing the possible routes of contamination that UD1022 can control, including internalized bacterial pathogens, or contamination on a conveyor belt or sponge roller.

Question:

Does your disruptive side prove challenging at home?

Answer:

I may have been told that before! (At least once or twice, ha!)

Question:

Why do you want to keep doing this work?

Answer:

Training the next generation of students is one of the best parts of my jobs. I love it when a student realizes his or her potential and gets excited about the research. I work with farmers who grow raw agricultural commodities, like leafy greens, that are at risk for contamination and the potential to provide these farmers with a tool to assist them to fight bacterial pathogens in their fields is so important. We must keep trying to find preventive measures that work.

Question:

What do you study, and what led you into this field?

Answer:

I now call myself a soil and environmental physicist, studying interesting agricultural and environmental problems related to soil and other natural systems.

I got into soil science as an undergraduate student because, at the time, I did not do so well at the highly competitive College Entrance Exam in China to get into a prestigious university to study math or physics.

Question:

Did you color outside the lines as a kid?

Answer:

I do not remember coloring. But I do recall when I took a Chinese painting class it was difficult for me to use the brush freely. I also tend to be better at the types of Chinese calligraphy that are ‘restricted’ in form than free styles. So if this question has to do with creativity, then I don’t ‘fit the bill’. However, I suspect what I described here has more to do with being a perfectionist than whether I am creative or not.

Question:

Can you recount the tipping point—the idea that produced your ‘aha!’ moment?

Answer:

There have been a few. The most recent one was in summer 2012 when I was attending the Gordon Research Conference on Flow and Transport in Permeable Media in Les Diablerets, Switzerland. This is an amazing conference I attend on a regular basis that attracts people from different fields despite what the title seems to imply.

I was listening to a talk by a medical researcher on something related to what hydrologists and chemical/petroleum engineers do, and my mind wandered to a call for proposals from the USDA addressing contamination of fresh produce by micro- organisms. I felt that I could contribute to the topic because of my many years of research on the interactions of colloids (viruses, bacteria, nanoparticles) with soil–fruits and vegetables would just be different in their surfaces from the soil surface. But as a soil physicist, I did not think I could apply for a grant from a food safety program.

Then it came to me: I just need to make a small change to my title, from soil physicist to soil and environmental physicist! The mental block was gone and I decided that I could work on any environmental system! I submitted a proposal to study attachment to and detachment of colloids and bacteria from produce surfaces, and the proposal was funded in 2013. It was a perfect ‘aha’ moment in a perfect location—the middle of the Swiss Alps.

Question:

Were there many naysayers and how did you navigate that?

Answer:

When I started at UD as an assistant professor, I spent most of research effort on studying the behavior of viruses in soil and groundwater systems. But my Ph.D. training was on organic contaminants. I was told that my virus research was not a ‘safe’ topic to work on before tenure because it is difficult and more time consuming to get results. I appreciated the advice but did not really listen. Overall, I have not run into many naysayers during my career so far.

Question:

Did anyone in particular inspire you to think differently?

Answer:

Definitely, Richard Feynman is my idol! He was a free-spirited physicist who had many interests (both academic or nonacademic) and his studies and research were driven by the pure joy of finding things out. He inspired me to think outside of the box, to not limit my thinking to artificial disciplinary boundaries, and to have fun with learning.

Question:

What has been most satisfying about your work? Most terrifying?

Answer:

The most satisfying has to do with the freedom of being in academia, which gives the opportunity to satisfy one’s curiosity about things and at the same time to make connections to important societal issues.

Question:

What is your favorite problem at the moment?

Answer:

My favorite problems at the moment is to study the rhizosphere: to improve our understanding on how physical, chemical, and (micro)biological processes work together to shape the functions of this very important albeit a small region that is so important for us to grow crops.

Question:

Does your disruptive side prove challenging at home?

Answer:

I have not thought of myself as someone who has a disruptive side, until now. I guess I must do some research and figure it out!

Question:

Why do you want to keep doing this work?

Answer:

Being able to learn new things, meeting very smart and wonderful people at conferences from all over the world, interacting and helping students to achieve their career and personal goals are some of the reasons that keep me going. I do have other interests (many have been put on hold) that I hope to have more time to pursue so retirement will not be bad.

MORE STORIES

From the Vice President for Research, Scholarship and Innovation

A disruptor prevents things from proceeding as usual. But that’s not always bad. In research and education, we’re always turning ideas and methods on their ear in the quest to learn something new…

Innovation In Motion

UD researchers partner with Reebok to build a “smart” sports bra — a sports bra engineered to actually do its job!

Disruptors

This issue of the University of Delaware Research magazine puts new faces on this idea of disruption, highlighting the innovative way our researchers are tackling complex problems. Learn about their work and what drives them and how the disruption they cause can produce real benefit for our world.

Bright Star

UD’s Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus is shining ever brighter with the nationally recognized Tower at STAR.

Test Your Knowledge: Innovation

As a growing research institution, the University of Delaware is a place where you’ll find new ideas constantly sparking solutions to challenges once deemed impossible.The wonder of innovation is all around us, but what do you really know about it? Try your hand at these questions.

Art In Science

Now in its fourth year, this annual exhibit offers a captivating glimpse into a vast world of discovery at the University of Delaware.

The Baltimore Collection

Something truly special emerged from a box that no one expected until Julie McGee, associate professor of Africana Studies and Art History, and her University of Delaware students got their hands on the 53 photographs inside.

Disruptors: Probing the Power of Paradox

A professor of management at UD’s Lerner College of Business and Economics, Wendy Smith focuses on how leaders and teams can effectively respond to contradictory agendas.

Disruptors: Defending Equal Access to Food

How does a new supermarket impact people who live nearby? Can healthy options be found in the little store down the street? These are questions that Allison Karpyn ponders regularly.

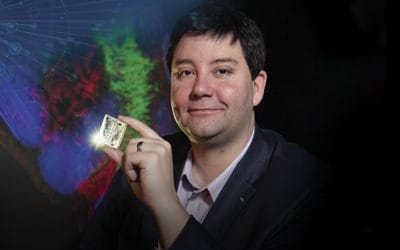

Disruptors: Cracking a Cell’s Secret Code

Jason Gleghorn has held a variety of jobs since college—teacher, firefighter, medic, engineer. Today, he’s an interpreter of sorts, too, deciphering the language that cells use to communicate in hopes of advancing new treatments for congenital birth defects, pediatric diseases and more.

Disruptors: Making Our Way

Professor of Africana studies at UD and an ordained elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Monica A. Coleman focuses on the role of faith in addressing critical social and philosophical issues.

Disruptors: Moving Forward with Autism

With skills in physical therapy, behavioral neuroscience and biomechanics, Anjana Bhat brings expansive expertise to her work developing creative therapies for those living with autism spectrum disorders.

Disruptors: Expanding Our World View

These co-founders of the Robotic Discovery Laboratories in UD’s College of Earth, Ocean and Environment manage a growing robotics fleet for use on land, in air and under the sea. They explore questions along the coast, at the poles and in deep regions of the ocean.

Honors

UD researchers have been recognized recently by the National Institutes of Health, American Political Science Association, TED Fellows program, National Science Foundation, National Academy of Inventors and the Gates Cambridge Scholarship program.

News Briefs

Check out some recent developments, from the launching of major research programs to address environmental and health issues in the First State, to the preservation of a pair of 1909 mittens with a hallowed history.

CONTACT

Tracey Bryant

Senior Director, Research Communications

Email: tbryant@UDel.Edu

SUBSCRIBE & CONNECT

The University of Delaware Research magazine showcases the discoveries, inventions and excellence of UD’s faculty, staff and students. Sign up for a free subscription.