DISRUPTORS

CRACKING A CELL’S SECRET CODE

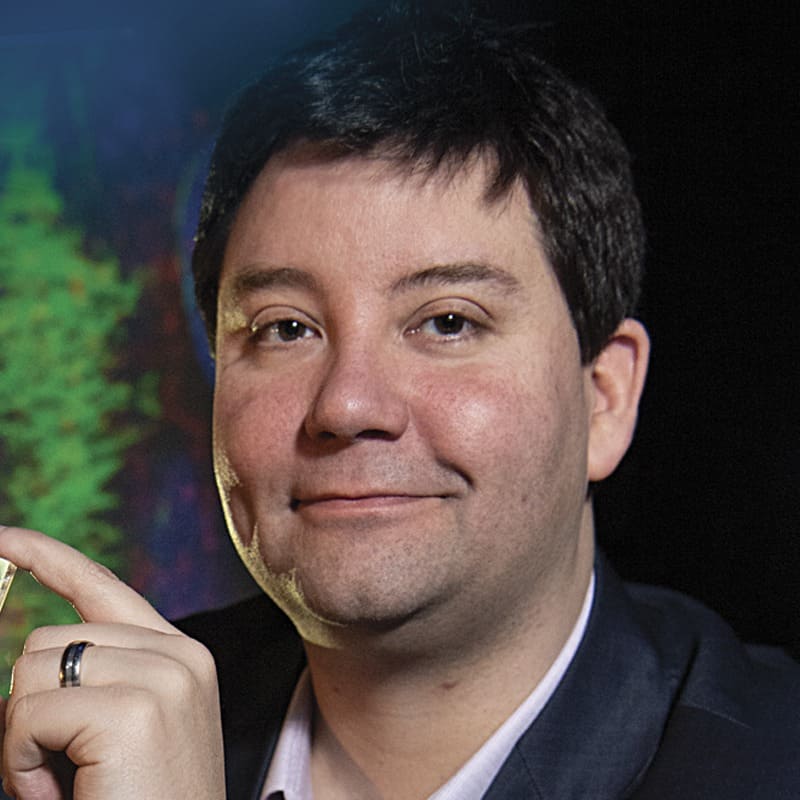

Jason Gleghorn has held a variety of jobs since college—teacher, firefighter, medic, engineer. Today he is an interpreter of sorts, too, deciphering the language that cells use to communicate.

No, Gleghorn doesn’t have a secret decoder pin like the one Ralphie Parker used in A Christmas Story to translate covert messages from Little Orphan Annie. Rather, he uses science and engineering to understand how cells talk and interact in hopes of advancing treatment options for congenital birth defects, pediatric diseases and more.

Jason Gleghorn

Department of Biomedical Engineering

MEET JASON

Jason Gleghorn is an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at UD. His research focuses on understanding how cells behave and communicate in order to assemble into functional tissues and organs, especially the lungs, kidney and blood vessels. This includes developing tiny 3D microfabricated and microfluidic tissue and organ models (lab-on-a-chip or organ-on-a-chip systems) to investigate the biophysical forces and chemical signals that drive tissue growth, homeostasis and disease.

Gleghorn also is exploring how mechanical forces influence cellular behaviors and interactions at the cell, tissue and organ-length scales to define new therapeutic approaches for regenerative medicine.

—Jason Gleghorn

Question:

What do you study, and what led you into this field?

Answer:

We study how multicellular systems build complex tissues and organs and how these change in disease. Essentially, we study how populations of cells talk to each other, deciphering the language (chemical signals, electrical impulses and physical forces) they use to communicate. My path has included studying engineering as an undergraduate, being a seventh-grade public schoolteacher, graduate school, working as a firefighter and medic, and completing two postdocs. I’ve trained in three different scientific disciplines and have practical experience performing emergency medicine in the field. These experiences inform my desire to work on translational research to develop treatments for congenital birth defects and conditions associated with premature birth, maternal and fetal health, and pediatric diseases.

Question:

Did you color outside the lines as a kid?

Answer:

I am an engineer, so I do like lines. However, much to my parents’ frustration, I would often take electrical/mechanical devices apart to see how they worked and often repurposed the parts for things I was building. As I got older, I could even reassemble the items so they were functional again.

Around age 5, I was notorious for taking apart click pens to steal the springs and internal parts. I would put the pens back together (now useless), then build little shooters and cars with the parts!

Question:

Can you recount the tipping point—the idea that produced your ‘aha!’ moment?

Answer:

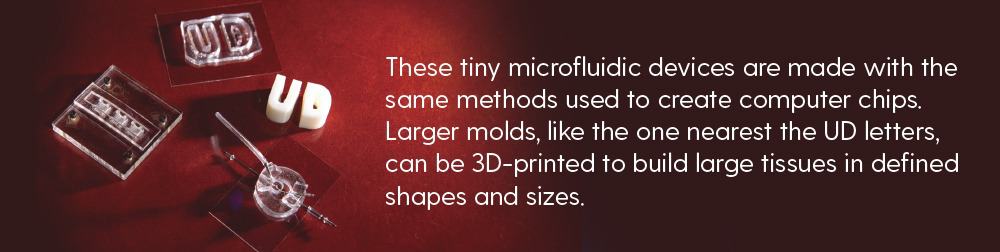

My undergraduate degree is in mechanical engineering. It wasn’t until I took a physiology course in my senior year that I became amazed at how the human body works. In grad school, I took gross anatomy, physiology and pathophysiology with the medical students. As I learned how we grow and develop in the womb, it dawned on me that, mechanically speaking, embryonic organs are microfluidic systems–teeny tiny fluid-filled tubes–that grow and remodel. This solidified my ideas that fluids and mechanical forces may interact with the biological, molecular and genetic programs during development to sculpt the growing organs. Since then I have been developing and using tools (e.g., micropatterning and microfluidics) to measure, perturb and watch these processes in complex tissues and organs to connect mechanical forces to the cellular programs driving development, homeostasis and disease.

Question:

Were there many naysayers and how did you navigate that?

Answer:

There are always naysayers and skeptics; however, you just have to believe in your ideas. I surround myself with extremely intelligent and creative students and collaborators grounded in very diverse fields of study. We leverage that diversity of training, perspective and opinion, and allow ourselves to be ruthlessly critical of any ideas we have so that the best ideas float to the top. I know that if we can tear apart and build on an idea within that framework, then even if it’s difficult, it’s an idea or approach that is important and it has a higher likelihood of success.

Question:

Did anyone in particular inspire you to think differently?

Answer:

I grew up in a hard working, blue-collar family full of elementary school teachers. I was one of the few in my family to go to college and the first to go to graduate school. I didn’t know anyone in science or research growing up. However, even though he didn’t go to college, my father is exceptionally clever and has an innate understanding and ability to build and fix things, usually in a jury-rigged, MacGyver-esque fashion. I think the many hours I spent with my dad as a kid gave me the exposure (and practice) of thinking this way–to really understand how something works and to laterally generate solutions to a problem. This is fundamentally how I think about problems today.

Question:

What has been most satisfying about your work? Most terrifying?

Answer:

Training my students is both the most satisfying and terrifying aspect of my work. The ability to work with diverse students, to help develop their critical thinking skills and abilities in the lab, and to watch them grow as people/engineers/scientists is extremely rewarding. They provide endless new ideas and contagious enthusiasm. However, it is also a tremendous responsibility to provide meaningful mentorship and the latitude students need to develop into successful innovators. This is a responsibility that I don’t take lightly. I believe I will continue to make significant contributions to scientific knowledge, but I know that some of my most important contributions will be the people I train. My trainees will continue to innovate and improve the world in their own way.

Question:

What is your favorite problem at the moment?

Answer:

It is hard to choose. We are working on a range of projects that I find deeply interesting, challenging and impactful. These projects span the gamut, from developing microfluidic systems to study virus-host interactions across multiple ecological contexts, to devising drug-delivery strategies to selectively treat mom or baby during pregnancy, to creating a microfluidic device for the culture of mouse lungs to study the molecular signaling (dys)regulation that occurs in premature babies when they are placed on a ventilator.

Question:

Does your disruptive side prove challenging at home?

Answer:

No, my wife keeps me in line. In all seriousness, I am fortunate to have a partner that is exceptionally supportive of me and my ideas. She also serves as a front-line screen for my crazy ideas and helps keep me grounded in reality. That said, I do think she is happy that I have my own laboratory space to tinker and build things so that I leave the appliances alone…

Question:

Why do you want to keep doing this work?

Answer:

I think that the problems we are working on are exceptionally challenging, but that we are looking at these problems in a different way such that we can really move the needle and generate solutions. Having had experience treating patients as a medic on an ambulance and interacting with parents and babies in the NICU, I know the direct impacts of the work we are pursuing for parents and kids who are given the scare of their lives with a grim diagnosis. If science tells us anything — it is that a life-changing discovery is just around the corner. We just need the courage to test some of our craziest ideas to try and make a real difference.

MORE STORIES

From the Vice President for Research, Scholarship and Innovation

A disruptor prevents things from proceeding as usual. But that’s not always bad. In research and education, we’re always turning ideas and methods on their ear in the quest to learn something new…

Innovation In Motion

UD researchers partner with Reebok to build a “smart” sports bra — a sports bra engineered to actually do its job!

Disruptors

This issue of the University of Delaware Research magazine puts new faces on this idea of disruption, highlighting the innovative way our researchers are tackling complex problems. Learn about their work and what drives them and how the disruption they cause can produce real benefit for our world.

Bright Star

UD’s Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus is shining ever brighter with the nationally recognized Tower at STAR.

Test Your Knowledge: Innovation

As a growing research institution, the University of Delaware is a place where you’ll find new ideas constantly sparking solutions to challenges once deemed impossible.The wonder of innovation is all around us, but what do you really know about it? Try your hand at these questions.

Art In Science

Now in its fourth year, this annual exhibit offers a captivating glimpse into a vast world of discovery at the University of Delaware.

The Baltimore Collection

Something truly special emerged from a box that no one expected until Julie McGee, associate professor of Africana Studies and Art History, and her University of Delaware students got their hands on the 53 photographs inside.

Disruptors: Probing the Power of Paradox

A professor of management at UD’s Lerner College of Business and Economics, Wendy Smith focuses on how leaders and teams can effectively respond to contradictory agendas.

Disruptors: Defending Equal Access to Food

How does a new supermarket impact people who live nearby? Can healthy options be found in the little store down the street? These are questions that Allison Karpyn ponders regularly.

Disruptors: Making Our Way

Professor of Africana studies at UD and an ordained elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Monica A. Coleman focuses on the role of faith in addressing critical social and philosophical issues.

Disruptors: Moving Forward with Autism

With skills in physical therapy, behavioral neuroscience and biomechanics, Anjana Bhat brings expansive expertise to her work developing creative therapies for those living with autism spectrum disorders.

Disruptors: Expanding Our World View

These co-founders of the Robotic Discovery Laboratories in UD’s College of Earth, Ocean and Environment manage a growing robotics fleet for use on land, in air and under the sea. They explore questions along the coast, at the poles and in deep regions of the ocean.

Disruptors: Harnessing Beneficial Microbes

So, what do a virologist, botanist and soil physicist have in common? This team from UD’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources is leveraging their collective expertise to ensure that our food supply is safe and abundant, now and in the future.

Honors

UD researchers have been recognized recently by the National Institutes of Health, American Political Science Association, TED Fellows program, National Science Foundation, National Academy of Inventors and the Gates Cambridge Scholarship program.

News Briefs

Check out some recent developments, from the launching of major research programs to address environmental and health issues in the First State, to the preservation of a pair of 1909 mittens with a hallowed history.

CONTACT

Tracey Bryant

Senior Director, Research Communications

Email: tbryant@UDel.Edu

SUBSCRIBE & CONNECT

The University of Delaware Research magazine showcases the discoveries, inventions and excellence of UD’s faculty, staff and students. Sign up for a free subscription.