A Matter of Justice and Preservation

The box was labeled “moldy photos”–a warning that its fragile contents would require special handling.

Something truly special emerged from that box, too, something no one expected until Julie McGee, associate professor of Africana Studies and Art History, and her University of Delaware students got their hands on the 53 photographs inside.

The work they did during McGee’s one-semester class in the fall of 2017— “Curating Hidden Collections and the Black Archive”—is a fascinating study in how to research, conserve and catalog a piece of history with few available guiding landmarks. And it laid the groundwork for future classes to do likewise.

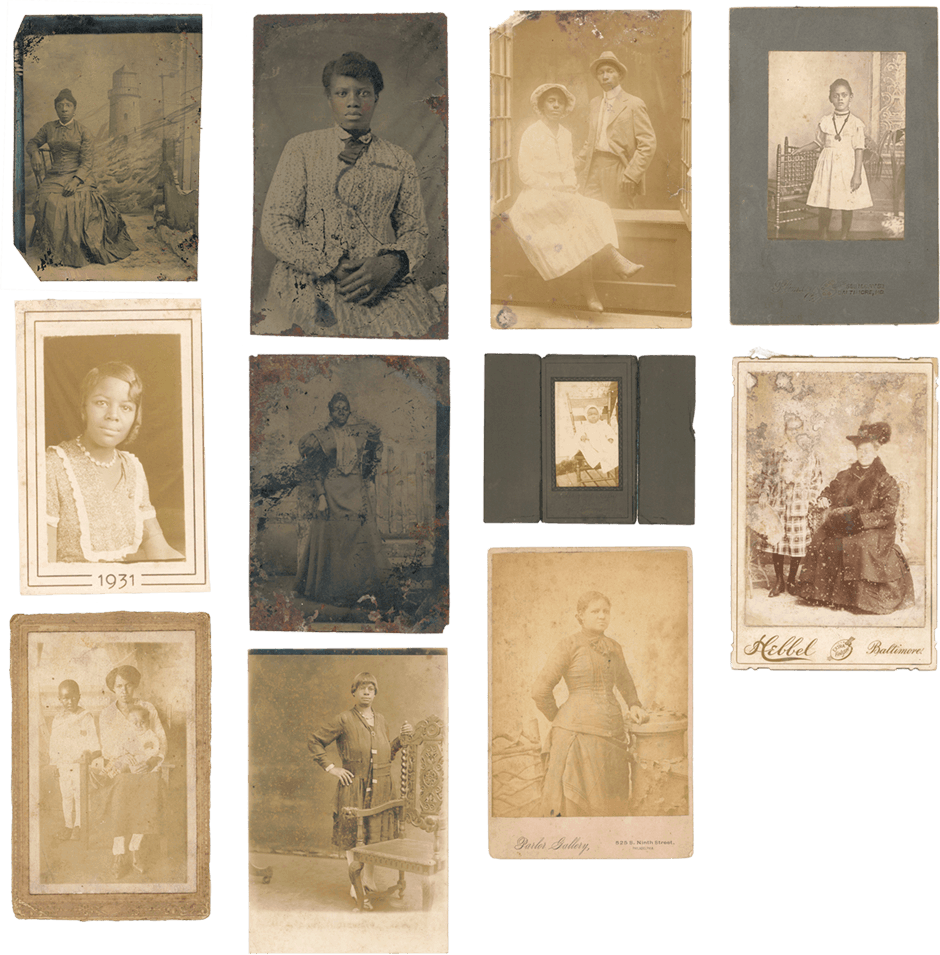

The photographs—mostly images of African Americans in the late 19th and early 20th century—brought much more than the technical challenges a conservator accepts when working with historic images and objects that need attention, as these surely did. They also raised questions of justice and pointed to systematic obfuscation of the stories and identities and truths of marginalized people.

The “Baltimore Collection,” as the photos now are called, doesn’t speak for itself but it has much to say to us.

“I work with and am often drawn to objects that exist in the realm of the unknown with the premise that they matter deeply, but for various reasons this meaning, and even their visibility, has been obscured. Part of the work is enabling them to be seen and providing context for ways of knowing,” McGee said.

Not fully, certainly, in this case—but far more than they would otherwise have been.

Hidden Histories

The photographs came to the University from an art history alumna, Jessica Porter, in 2001. Her late father had found them abandoned in Maryland, McGee said, and they arrived at UD with little or no explanation. A variety of photograph types were in the box, including tintypes, albumen prints, matte collodion prints, silver gelatin printing-out prints (POP), silver gelatin developing-out prints (DOP) and one halftone.

Almost half of them were made in Baltimore, the others in Philadelphia, Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Washington, D.C.

McGee, a curator with special expertise in African-American art, said the photographs had been evaluated when they reached the University. They were assigned the number “9999.0910,” a category that indicates a preliminary status as objects of educational quality or, in some cases, disposable if they cannot be stabilized or salvaged.

When she arrived at UD in 2008 as curator of African-American art for University Museums, she started to explore everything in the University’s custody.

“I was trying to get a better grasp of the totality of the collection that represents African-American culture,” she said. “Is there anything that is not cataloged yet—anything we may have overlooked? Sure enough, there was a box of ‘moldy photographs.’ The mold was no longer active, but the photographs clearly needed conservation … and were in various stages of deterioration.”

They also raised far more questions than they could possibly answer—a challenge for curators and those who capture and catalog the metadata that explain each photograph and its context.

What should be done with these photographs? Should they be digitized, which—in effect—creates another collection? How could they be made accessible to others? How do you catalog the unknown? How do you describe the race of a person? Should you? Why?

McGee built a course around this box of photographs and the questions they represented—“Curating Hidden Collections and the Black Archive,” an interdisciplinary seminar that included 11 students drawn from history and museum studies, art history, the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture and Africana studies.

The work started with students trying to learn as much as possible about each item and also trying to describe the photographs and whatever they learned about them in accurate terms.

Those conventions and the words and details included in such data are under great scrutiny in this field—in a transformative period, perhaps.

“We looked at the cataloging and metadata schema used by varied institutions that had similar collections of photographs of unidentified people, including the Library Company in Philadelphia, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the Library of Congress,” McGee said. “And the students elected to diverge from some of the standard modes of visual description.”

For example, many photograph data points have historically described a person’s race only if they are not white. Whiteness has not typically been described in the title of most photographs cataloged.

The descriptive title is critical, though, because it generates the citation. It will be the priority text in a catalog and will often determine what people find when they do digital searches.

“Descriptive titles—bracketed to indicate they came from a cataloger—can be updated over time to reflect greater knowledge about the object and sensitivity to the biases they reflect. For example, 19th-century photographs of black women holding white infants, historically described as ‘nannies,’ are being revised by institutions,” McGee said. “The difference between ‘nanny’ and ‘unidentified enslaved person holding their white charge or unidentified child’ is significant. Transparent cataloging, like that at the Library of Congress, makes note of the changes in descriptive titles by retaining the older titles in the full record. When we use digital collections we rarely think about this level of curation. We simply accept the data provided.”

Students developed a database for the collection, using Artstor, the enormous digital platform that holds a trove of images from museums around the world. They filled in appropriate category fields and created new reports that included conservation notes for the photographs. Those notes were created by students who worked on the collection during Prof. Debra Hess Norris’ Winter Session class in the highly regarded Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation.

“It was especially nice for our students to have the opportunity to stabilize a collection that had been studied intently by other graduate students at UD,” said Norris, Unidel Henry Francis du Pont Chair of Fine Arts. “Many of these portraits were severely water- and mold-damaged and they required consolidation and cleaning, often under magnification.

“The conservation treatment of the Baltimore Collection was a wonderful project—connecting teaching with preservation and a powerful collection—one my students and I will always treasure.”

If you have information about any of these photographs, please contact Amanda T. Zehnder, chief curator of Special Collections and Museums at the University of Delaware, at azehnder@udel.edu.

Searching for Clues

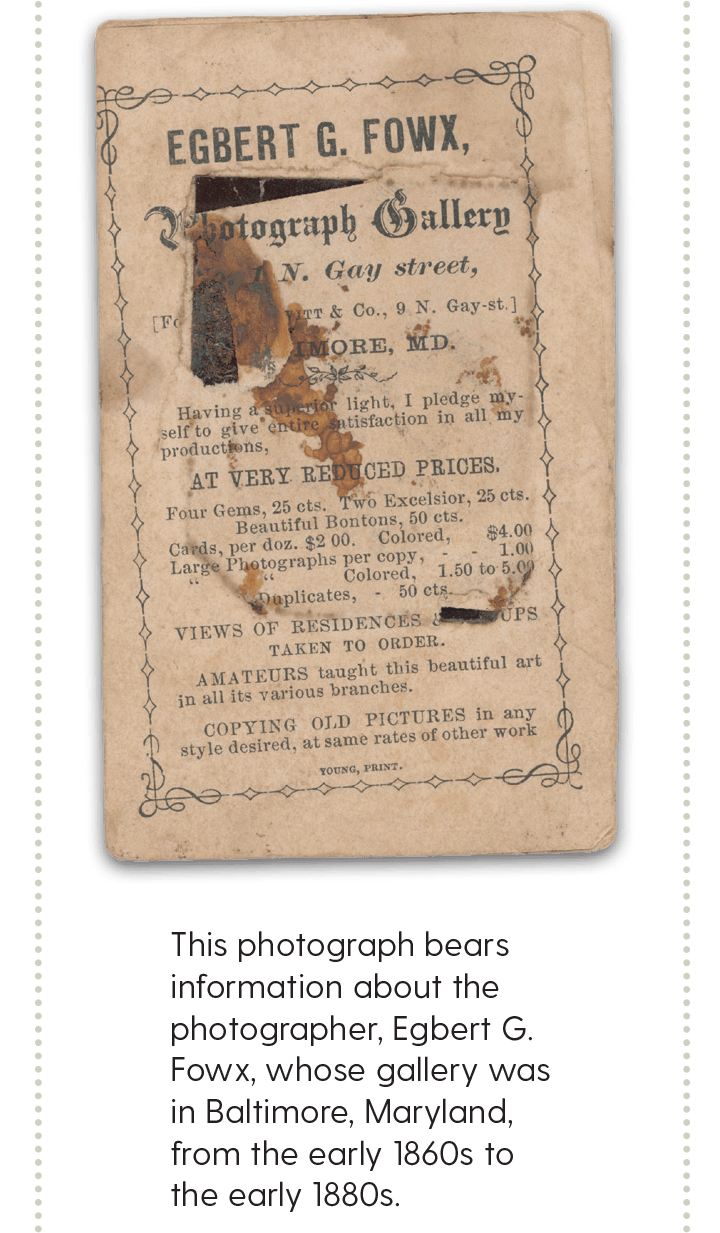

Some photographs had the name of a studio stamped on them, offering clues to the time and place the sitters could have been there. Students pursued such clues to see if they could find more information.

Dorothy Fisher, a doctoral student in art history, saw the photographer’s name and address on the back of one of the photographs she was working with—the faded, barely-there image of a woman in a white dress on a residential street of Baltimore row houses. The front steps of the house were white.

“Even with a magnifying glass, you can’t see the woman’s face,” Fisher said. “You can see part of a tree, part of a street lamp. But you can clearly see those white steps.

“In my hubris, I was convinced I would find which residential street this was.”

Her quest was frustrated by one stubborn fact of Baltimore history.

“Those row houses with white steps could be anywhere in the city of Baltimore,” she said. “There is a tradition of white steps in the city.”

As the class worked, they developed a website and used it to share their thoughts about the images they were working with.

Ethan Barnett, a doctoral student in the African American Public Humanities Initiative, wrote a series of powerful poems in his post titled “Dear ‘Unidentified’ woman in photo 31.”

Photo 31 is a portrait of an African- American woman and a white boy on a porch. The woman is seated, holding a teddy bear, and the child is standing beside her, looking up at her face. In the prologue to his poetry, Barnett asks about their connection. Are they neighbors? Related? Is she a caretaker?

Barnett says his poems are a response to “the historical erasure of blackness within photographs and the distribution of power that whiteness holds onto mercilessly within the world.”

His poems develop with extraordinary voice, starting with a sort of polite distance and moving urgently toward familiar tones to deliver a litany of awful news from the 21st century, where the debate apparently still rages over whether #BlackLivesMatter.

Legacies and Histories

Of course, there are debates over whether any of this matters. Every family has photographs of people they can hardly identify anymore, images that may have limited value even to those who are attached to them in some kinship way.

But these point to something else, McGee said.

“What the Baltimore Collection represents to me is that we ‘privilege’ objects that are in great condition that have legacies and histories that can be recorded,” she said. “And those are things that have provided dominant resource material for that which we can study.

“The Baltimore Collection gives us something you don’t often find visible in public collections—objects and histories that have not been extensively researched. Its digitization and visibility contribute to a larger narrative related to ‘hidden’ collections and what they have to teach us.”

In other words, there are many holes in our history and many of those holes were deliberately gouged. As diversity increases—in thought, identity and experience—the gaps and the sense that something precious has been lost or hidden become more evident. Curators can address that in significant ways and students at UD have added a sense of urgency to that effort.

In the Baltimore Collection, lives are captured at a moment in time, within a specific context, carrying a unique reality. They are now preserved for our education and enrichment, housed in an acid-free box and marked “The Baltimore Photographic Portrait Collection: Preserved.”

MORE STORIES

From the Vice President for Research, Scholarship and Innovation

A disruptor prevents things from proceeding as usual. But that’s not always bad. In research and education, we’re always turning ideas and methods on their ear in the quest to learn something new…

Innovation In Motion

UD researchers partner with Reebok to build a “smart” sports bra — a sports bra engineered to actually do its job!

Disruptors

This issue of the University of Delaware Research magazine puts new faces on this idea of disruption, highlighting the innovative way our researchers are tackling complex problems. Learn about their work and what drives them and how the disruption they cause can produce real benefit for our world.

Bright Star

UD’s Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus is shining ever brighter with the nationally recognized Tower at STAR.

Test Your Knowledge: Innovation

As a growing research institution, the University of Delaware is a place where you’ll find new ideas constantly sparking solutions to challenges once deemed impossible.The wonder of innovation is all around us, but what do you really know about it? Try your hand at these questions.

Art In Science

Now in its fourth year, this annual exhibit offers a captivating glimpse into a vast world of discovery at the University of Delaware.

Disruptors: Probing the Power of Paradox

A professor of management at UD’s Lerner College of Business and Economics, Wendy Smith focuses on how leaders and teams can effectively respond to contradictory agendas.

Disruptors: Defending Equal Access to Food

How does a new supermarket impact people who live nearby? Can healthy options be found in the little store down the street? These are questions that Allison Karpyn ponders regularly.

Disruptors: Cracking a Cell’s Secret Code

Jason Gleghorn has held a variety of jobs since college—teacher, firefighter, medic, engineer. Today, he’s an interpreter of sorts, too, deciphering the language that cells use to communicate in hopes of advancing new treatments for congenital birth defects, pediatric diseases and more.

Disruptors: Making Our Way

Professor of Africana studies at UD and an ordained elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Monica A. Coleman focuses on the role of faith in addressing critical social and philosophical issues.

Disruptors: Moving Forward with Autism

With skills in physical therapy, behavioral neuroscience and biomechanics, Anjana Bhat brings expansive expertise to her work developing creative therapies for those living with autism spectrum disorders.

Disruptors: Expanding Our World View

These co-founders of the Robotic Discovery Laboratories in UD’s College of Earth, Ocean and Environment manage a growing robotics fleet for use on land, in air and under the sea. They explore questions along the coast, at the poles and in deep regions of the ocean.

Disruptors: Harnessing Beneficial Microbes

So, what do a virologist, botanist and soil physicist have in common? This team from UD’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources is leveraging their collective expertise to ensure that our food supply is safe and abundant, now and in the future.

Honors

UD researchers have been recognized recently by the National Institutes of Health, American Political Science Association, TED Fellows program, National Science Foundation, National Academy of Inventors and the Gates Cambridge Scholarship program.

News Briefs

Check out some recent developments, from the launching of major research programs to address environmental and health issues in the First State, to the preservation of a pair of 1909 mittens with a hallowed history.

CONTACT

Tracey Bryant

Senior Director, Research Communications

Email: tbryant@UDel.Edu

SUBSCRIBE & CONNECT

The University of Delaware Research magazine showcases the discoveries, inventions and excellence of UD’s faculty, staff and students. Sign up for a free subscription.