IMAGINE THIS SCENE IN ANCIENT POMPEII

“There is a crowd of people, including free men, women and children, slaves and their owners. A rich guy wearing a toga rides in a litter carried by slaves. The people move to the sides, as the litter comes through. People are carrying water home from the fountains, taking clothing to the fullery for laundering. They are doing their marketing—getting bread at the bakery; fruit and vegetables such as figs, grapes and apples, olives, peas and beans; and perhaps some garum, a popular fish sauce. Others may be shopping for jewelry, new plates for the banquet next week, flower garlands for the coming festival. Wealthy people have their entourage around them, including their slave attendants. A procession is on its way to the forum. Slaves are bringing fresh donkeys to the bakeries to keep the grindstones turning, and pigs and sheep are being brought to market. The street is filled with the strong odors of bread baking and wine making, urine from the collection pots along the street, animal dung and household garbage. The Romans relied on the rain to wash the filth and garbage away.”— Lauren Petersen, professor of art history

Slaves’ lives emerge from ancient ruins

A groundbreaking new approach brings the forgotten into focus

“Detfri slave of Herennius Sattius” and “Amica slave of Herennius” reads the terra-cotta tile. It was discovered atop the ancient temple in Pietrabbondante, a town tucked into the bare rock and evergreen-covered mountains more than 100 miles east of Rome.

The reddish clay is inscribed with the slaves’ names in Oscan and Latin, two languages of the period. But that’s not all. The tile also carries their footprints.

Virtually no footprints from the inhabitants of ancient Rome survive, and to have those of slaves—the lowest rung of Roman society—is particularly intriguing, says Lauren Hackworth Petersen, professor of art history at the University of Delaware.

“It’s a wonderful, subversive act,” says Petersen. “It also tells us some slaves could write, and that they weren’t fixed to one location, such as in the kitchen. They were mobile, moving through their daily landscapes. This is largely unrecognized in ancient and modern accounts of Roman cities and streets.”

Slaves were present nearly everywhere in ancient Roman society. Some estimates place the Roman Empire’s population at 60 million in its heyday (A.D. 98–117), with at least a quarter of that total slaves (15 million). Yet, Petersen says, these men, women and children remain largely invisible in both guidebooks and scholarly works.

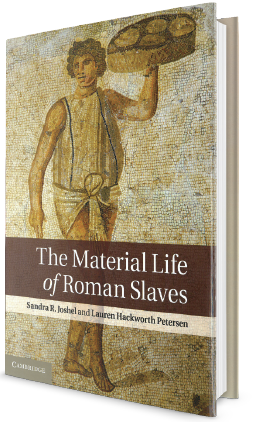

In 2007, Petersen and colleague Sandra Joshel, a history professor at the University of Washington, joined forces to make the invisible visible—by seeing slaves where Roman law, literature and art say they were present and reconstructing their lives from the archaeological ruins of the houses, workshops, streets and country villas that slaves inhabited.

The Material Life of Roman Slaves, published in 2014 by Cambridge University Press, showcases the duo’s pioneering approach. It has been recognized with two 2015 PROSE Awards, for best scholarly book in the humanities and best scholarly book in the classics and ancient history.

“The presence of Roman slaves should be visible in the material world that they lived in,” Petersen says. “Yet scholarly practices unwittingly ‘unsee’ slaves by focusing solely on the archaeological remains from the slaveholder’s point of view. We’ve tried to weave together historic texts and archaeology to begin to see their lives.”

Lauren Petersen studies the remains of a bakery in Pompeii. The bakeries were among the most grueling places for a slave to work.

A new vision for recreating the past

Petersen and Joshel took their first trip together to Pompeii in 2008, challenging themselves to re-envision the city from a slave’s perspective as they walked through the excavated remains of Mt. Vesuvius’ wrath. When the volcano spewed deadly gas and buried the ancient coastal resort and its people in a sea of ash in A.D. 79, Pompeii became a time capsule of ancient Roman life.

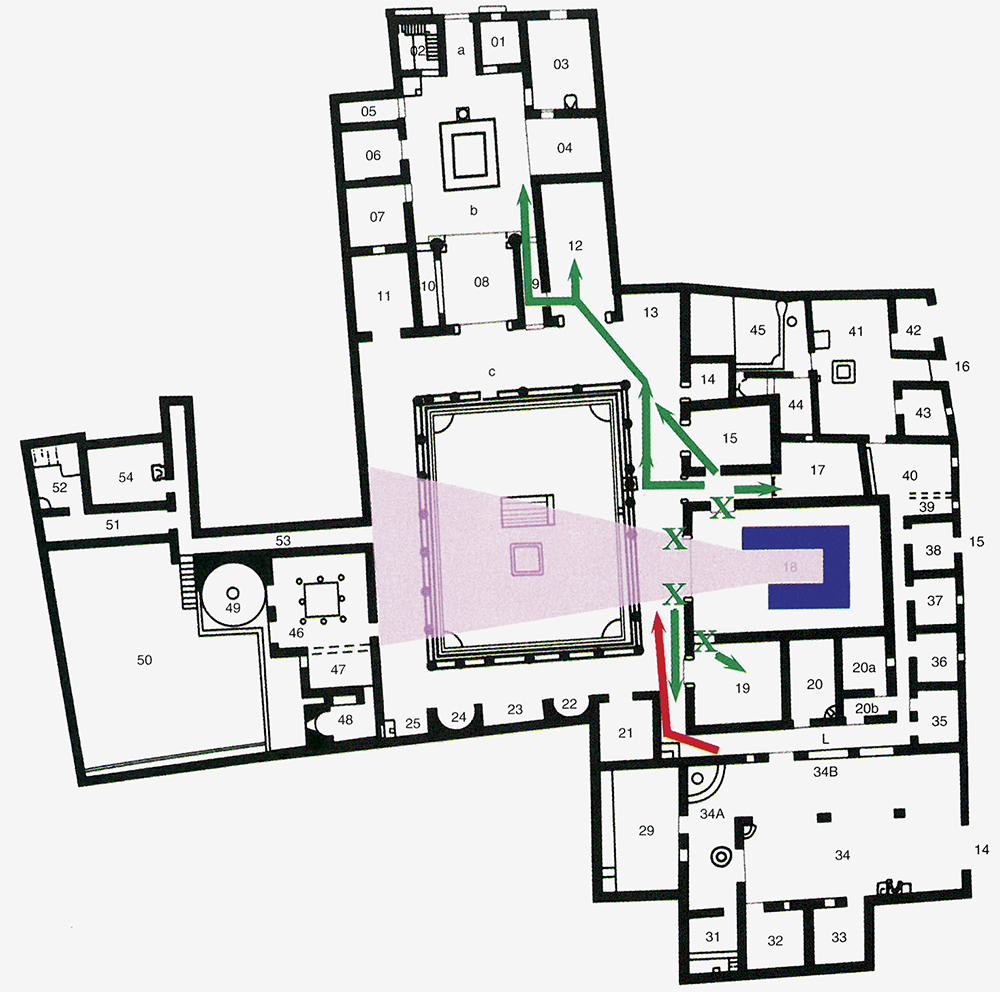

In the massive House of the Menander, which occupies nearly a city block at Pompeii’s center, Petersen stood in the main dining room where the slave owner would be positioned during a banquet, and Joshel played the role of the slave bringing refreshments into the dining room or planning the best route to slip out to the fountain in the square or the bar a few blocks away.

“It was eye-opening,” Petersen says. “Slaves were all over the house, so what would be their path to the dining room? What would it mean to carry trays there? In a number of writings, slaveholders complain about slaves being idle, of shirking work, of working too slowly. So what would that look like in this house?”

The authors’ resulting “Plan of the House of the Menander”—among the book’s 186 figures, photos and maps—marks the routes for possible slave “shirking tactics” during a banquet in the dining room. The area within the slave owner’s view is marked, along with the servant stations and possible shirking routes. Pathways are identified for “interrupting slaves” who might interrupt the festivities and divert the slave owner’s attention, allowing a fellow slave to slip out into the street.

After 9 p.m. in ancient Pompeii, the realm of speculation really sets in, Petersen says. “People were moving around, going to the bars, the taverns, the brothels. In the bigger houses, slaves might have made certain agreements with the doorkeeper to slip out into the night.”

Roman history also tells of objects falling from rooftops at night, injuring and sometimes killing people walking below. Could slaves have been the perpetrators?

“The second stories of these buildings are a big mystery because most of them were destroyed long ago,” Petersen says.

Roman archaeology holds tight to its truths, according to Petersen. But in intertwining the practices of art history, archaeology and history, she and Joshel offer the conservative classics a new approach to exploring and preserving the past.

Petersen was a business major in college with her sights set on the junior executive program at Macy’s when she says she learned a great lesson: “Let life happen to you.”

On a study abroad program to Assisi in her junior year, she developed a passion for Italy. In her senior year, she took two art history classes. Two days before graduation, she listened closely as one of the commencement speakers urged, “Go and give something back.”

“It was then that I decided I didn’t want to sell clothes to rich kids,” Petersen says. “I told myself, ‘I’m going to be an art historian and focus on Italian art.’”

After completing her master’s at Florida State University and a doctorate at the University of Texas, Austin, Petersen joined the UD faculty in 2000. She’s since written numerous articles, has co-edited the book Mothering and Motherhood in Ancient Greece and Rome (2012), and authored another book, The Freedman

in Roman Art and Art History (2006). She also is director of graduate studies for the Department of Art History.

“My interest has always been in giving a voice to people silenced,” Petersen says. “My hope, wish, desire is for people to go to Pompeii and Rome, and when they tour those ancient cities and villas, understand who made that life of luxury possible.”

A Slave’s Lot in Life

House of the Menander in Pompeii is named for this fresco, believed to portray the Greek playwright Menander. Historians speculate that the house, which spans nearly a city block, may have been owned by a very wealthy man at the time of Mt. Vesuvius’ eruption in A.D. 79.

Slavery in ancient Roman times wasn’t based on race, ethnicity or economic status. It followed a simple, punishing rule: Whomever the Romans conquered became their slaves.

A long list of nations that make up present-day Europe, Africa and the Middle East got consumed by the Roman Empire, which began with the founding of Rome in 753 B.C. and fell more than seven centuries later in A.D. 476. The human spoils of these conquests built the empire’s economy with their backs. In the countryside, some poor souls were bred for a life of servitude.

Under Roman law, slaves were property. They had no rights. Although owners were required to provide their slaves with food and shelter, UD’s Lauren Petersen says it’s questionable if the law was policed.

“A slave’s life was filled with long days of hard work. Many were beaten regularly and subjected to other brutality,” Petersen says.

Although slaves could not legally marry, many did. These unions were not recognized in court, and their children became slaves at birth. Such families could be split up at any time.

The slaves’ purpose in life was to keep their owners satisfied, whether growing wheat on farms outside the cities, mining gold and silver, cutting marble for the luxury two-story villas of the wealthy elite, carrying water home from the fountains, working in the disease-infested brothels.

The better assignments? Being a poet or musician in the retinue of the most powerful Roman—the emperor. Or having another less physically demanding position in domestic life, as the accountant entrusted to keep the household records or as the hairdresser for a rich family.

The worst jobs were in the mines, “where you’d never have a chance of freedom,” Petersen says, and in other places that might surprise you.

Take the fullery, or laundry. Fulleries cleaned clothes ranging from the tunic (worn by both free men and slaves) to the stola (worn by women) to the toga, which could be worn only by free men. The toga wasn’t worn frequently, however, Petersen says, because it took over 10 feet of material to make one, and it was hard to keep clean in the heat and dust.

Urine—high in ammonia—was used as the primary cleaning agent. It was collected in large clay jars outside of homes and at public urinals.

Dirty clothing would be soaked in a tub of urine and water in a fulling stall. A worker would stand barefoot in the tub, hands holding onto the stall sides, and stomp on the clothes. Another worker standing in a large basin would rinse the clothes, beating them against the basin sides to wring them out. A mural in Pompeii shows baskets resembling bird cages over which wet clothes were then draped for drying and finishing. Sulfur would be burned at the bottom of these cages to whiten the clothes.

“Can you imagine the heat and odor these slaves had to bear, and the blisters on their feet?” Petersen says.

The smell of baking bread is unquestionably better than nostril-burning ammonia, yet literary writings of the day paint a grim picture of the treatment of both man and beast in the bakeries.

In the House of the Baker at Pompeii, Petersen and Joshel map out the work that must take place in and around the mill area to understand the movement of slaves. A number of workers would have been focused on goading the donkeys to walk in circles all day to grind the grain into flour.

In his story of a young man who is magically turned into a donkey, the writer Apuleius describes how the constant circling of the mill disfigures the donkey’s hooves, and whippings leave the animal’s flanks bare. Likewise, welts mark the slaves’ skin, their foreheads are branded, heads shaved and feet shackled. Flour coats them—“like boxers covered in sand when they fight in the arena,” Petersen says.

Attempting to flee a life of hardship was not without its risks. Slaves were valuable property and owners did not take such losses lightly.

Escaped slaves were sought relentlessly. “Billboards” painted on the outside walls of houses facing major streets might announce missing slaves along with gladiatorial combat and upcoming elections.

Once recaptured, many slaves were branded with an “FVG” on their forehead for “fugitivus” or “fugitive.”

Kind owners frequently set their slaves free, Petersen says, while some other owners gave their slaves an allowance and let them purchase their freedom.

“Freed slaves could run a business for a former owner and become quite wealthy, which was of concern to the elite,” Petersen says. “When citizens started to tap former slaves on account of their wealth, it set the stage for local politics.”

MORE STORIES

ADVANCE-ing UD

Seven faculty members are highlighted in this issue of UD Research. Indeed, there are commonalities among them—a steadfast commitment to excellence, unrelenting intellectual curiosity, mentors and role models who inspire, and a disdain for the status quo. I encourage you to read their stories to learn about their inspirations, the challenges they have faced and the scope and quality of their scholarly endeavors.

Women of Research

Extraordinary research is underway at the University of Delaware, and women are all over it. We profile seven researchers who offer insight into their work—from coral reefs to corporations—what hurdles they have cleared and what keeps them moving forward.

Danielle Dixson

A chance encounter with a tour guide at the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago is what sparked Minnesota native Danielle Dixson’s interest in marine biology. “I was 5 years old and the guide gave me a book for asking a clever question about whales,” she says.

Liz Farley-Ripple

Elizabeth Farley-Ripple did not set out to become an education researcher. As an undergraduate at Georgetown University, she started out majoring in Latin American Studies. Then came Professor Bill McDonald’s sociology course focusing on research methods. “I had an aha moment,” says Farley-Ripple. “I realized I could have an impact—and actually apply the ideas I had been reading about.”

Jennifer Joe

Jennifer Joe, the Whitney Family Professor of Accounting in the Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics, attributes positive experiences with her professors in college as the impetus for her pursuit of an academic career.

Rhonda Prisby

Rhonda Prisby had a plan for her master’s degree in exercise physiology. She expected to work in a cardiac rehabilitation clinic. Then a professor mentioned something she hadn’t considered—her potential as a researcher.

Angelia Seyfferth

Having had the chance to conduct research taking water samples on the Chesapeake Bay early in her undergraduate studies, Angelia Seyfferth, assistant professor in the Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, is hoping to pass her enthusiasm for research to young scholars in her lab.

Margaret Stetz

As a scholar with diverse interests from 19th-century British literature to military history and fashion studies, and who shares her work in a variety of academic and community forums, Margaret D. Stetz might be expected to have difficulty summarizing what she does.

Cathy Wu

For Cathy Wu, becoming a bioinformatics expert was kind of accidental. Armed with a Ph.D. in plant pathology and a postdoc in molecular biology, she followed her husband on a job move to Tyler, Texas, in the mid-1980s, but was unable to land a good faculty position there.

Never underestimate the power of good mentoring

A few years ago, a newly hired female faculty member had the following experience: A male colleague responded to her hallway greeting by saying hello and adding, “I hope everyone is making you feel welcome.”

Spin in spins out innovation

The University of Delaware’s “Spin In” program, founded, managed and trademarked by the Office of Economic Innovation and Partnerships, connects University undergraduate students with community entrepreneurs and early-stage startups to give them an inside look at business innovation in action and a chance to apply what they’re learning in real-life situations.

Making it clear

For the past three years, almost 90 educators from around Delaware and Maryland have been working with scientists and environmental experts from the University of Delaware and the University of Maryland. The goal is to develop a richer understanding of climate change and build effective activities and instruction plans to help their students understand the data and find potential solutions.

Solar Strong

The vast majority of the sun’s extraordinary power remains out of reach—absorbed, deflected or otherwise inaccessible to today’s power-hungry masses—but University of Delaware researchers continue their quest to capture more, store more and deploy it more efficiently.

Honors

• Dugan named Truman Scholar

• Overby elected to board of Oak Ridge consortium

• Backbone of the profession

Fearsome Fridays

Tom Fernsler, “Dr. 13,” now retired from the Delaware Center for Teacher Education, knows a lot about Friday the 13th. Do you? Take our quiz and find out!

News Briefs

• Changing the color of light

• What’s it really mean if a CEO is greedy?

• Research All-Stars field new findings