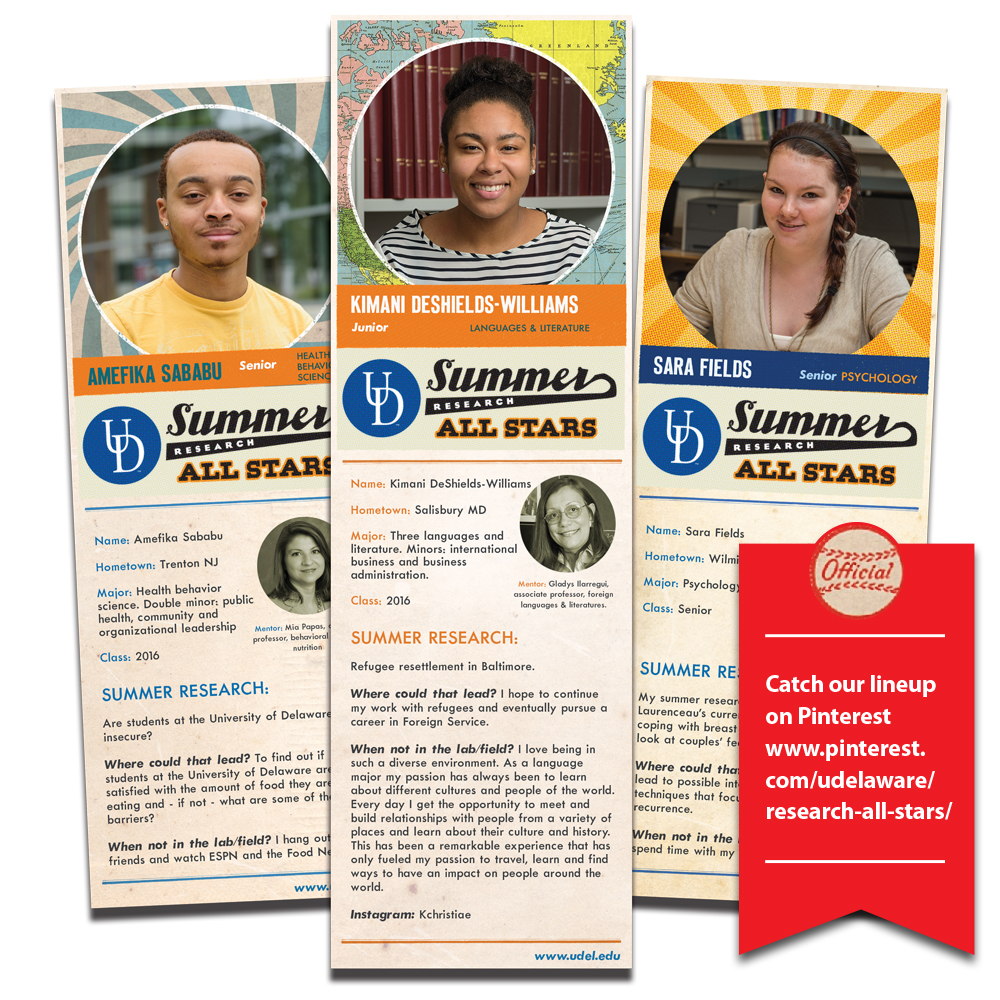

Research All-Stars field new findings

They explored everything from Jamaica’s dancehall music to how optics can provide navigational aid in thick fog or smoky conditions, the difference in how assault victims report crimes to police in the United States, Argentina and South Africa, and how the visual arts can enhance third-grade English curriculum.

They served international refugees living in Baltimore, analyzed the water quality of Brandywine Creek, studied how bone pain from metastatic prostate cancer might be addressed and looked for ways to keep dairy cattle feed from spoiling.

In mid-August, the University hosted its sixth annual “Celebratory Symposium,” where more than 400 students spent a day at the Patrick Harker Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering (ISE) Lab explaining details of their work and where it might lead. Students from almost three dozen other institutions participated, visiting from such schools as Amherst, Columbia, Cornell, Delaware State, Duke, Georgia State, Western Oregon, Penn State and Rochester, to name a few.

“This is the University of Delaware at its best,” said Iain Crawford, director of Undergraduate Research and Experiential Learning. “And this is our favorite day of the year. A lot of what they do is invisible to us—they’re off in their labs or with community partners. This is one day where we all get together and see the amazing work everyone has been doing.”

Changing the color of light

They won’t be tinkering with what you see out your window: no purple days or chartreuse nights, no edits to rainbows and blazing sunsets. Their goal is to turn low-energy colors of light, such as red and orange, into higher-energy colors, like blue or green.

Changing the color of light would give solar technology a considerable boost. A traditional solar cell can only absorb light with energy above a certain threshold. Infrared light passes right through, its energy untapped.

However, if that low-energy light could be transformed into higher-energy light, a solar cell could absorb much more of the sun’s clean, free, abundant energy. The team predicts that their approach could increase the efficiency of commercial solar cells by 25 to 30 percent.

The research team, based in UD’s College of Engineering, is led by Matthew Doty, associate professor of materials science and engineering and co-director of UD’s Nanofabrication Facility. Doty’s co-investigators include Joshua Zide, Diane Sellers and Chris Kloxin, all in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering; and Emily Day and John Slater, both in the Department of Biomedical Engineering.

A ray of light contains millions and millions of individual units of light called photons. The energy of each photon is directly related to the color of the light—a photon of red light has less energy than a photon of blue light. You can’t simply turn a red photon into a blue one, but you can combine the energy from two or more red photons to make one blue photon.

This process, called “photon upconversion,” isn’t new. However, the UD team’s approach to it is.

They want to design a new kind of semiconductor nanostructure that will act like a ratchet. It will absorb two red photons, one after the other, to push an electron into an excited state when it can emit a single high-energy (blue) photon.

These nanostructures will be so teeny they can only be viewed when magnified a million times under a high-powered electron microscope.

“Think of the electrons in this structure as if they were at a water park,” Doty says. “The first red photon has only enough energy to push an electron half-way up the ladder of the water slide. The second red photon pushes it the rest of the way up. Then the electron goes down the slide, releasing all of that energy in a single process, with the emission of the blue photon. The trick is to make sure the electron doesn’t slip down the ladder before the second photon arrives. The semiconductor ratchet structure is how we trap the electron in the middle of the ladder until the second photon arrives to push it the rest of the way up.”

The UD team has shown theoretically that their semiconductors could reach an upconversion efficiency of 86 percent, which would be a vast improvement over the 36 percent efficiency demonstrated by today’s best materials. What’s more, Doty says, the amount of light absorbed and energy emitted by the structures could be customized for a variety of applications, from lightbulbs to laser-guided surgery.

As part of the project, the team aims to develop an upconversion nanoparticle that can be triggered by light to release its payload. The goal is to achieve the controlled release of drug therapies even deep within diseased human tissue while reducing the peripheral damage to normal tissue by minimizing the laser power required.

“This is high-risk, high-reward research,” Doty says. “High-risk because we don’t yet have proof-of-concept data. High-reward because it has such a huge potential impact in fields from renewable energy to medicine. It’s amazing to think that this same technology could be used to harvest more solar energy and to treat cancer.”

What’s it really mean if a CEO is greedy?

But how do you define greed? Are compassionate CEOs better for business? How do you know if the leader is doing more harm than good? And can anybody rein in the I-Me-Mine type leader anyway?

University of Delaware researcher Katalin Takacs Haynes and three collaborators—Michael A. Hitt and Matthew Josefy of Texas A&M University and Joanna Tochman Campbell of the University of Cincinnati—have chased such questions for several years, digging into annual reports, comparing credentials with claims and developing useful definitions that could shed more light on the impact of a company’s top leader on employees, business partners and investors.

“We tried to look at what we think greed is more objectively,” said Haynes, associate professor of management in UD’s Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics. “What we’re trying to do is clean up some of the definitions and make sure we’re all talking about the same concepts.”

The researchers offer plenty of evidence that some leaders are insatiable when it comes to compensation. How much is too much? They don’t put a number on it. But they do add plenty of nuance to the question and point to a mix of motivations that goes beyond raw greed.

“It’s not for us to judge what too much is for anybody else,” said Haynes, “but we can see when the outcome of somebody’s work is the greater good, and when it is not just greed that is operating in them.”

Greed seems all too apparent to many workers. The recent recession left millions without jobs and many companies sinking into a sea of red. At the same time, though, stunning bonuses and other perks were landing in the laps of people at the helm.

Haynes, who joined the UD faculty in 2011, has found the range of pay within companies intriguing, too.

“Why is it that in some companies there is a huge difference between the pay of the top executive and the average worker or the lowest-paid employee and in other companies the pay is a lot closer?” she said.

Many a minimum-wage worker, making $15,080 per year, has wondered that, and so have those in the middle class, who may work a year to make what some CEOs make in a day.

But if you make more than anyone else does that mean you’re greedy?

Haynes and her collaborators go to the data for answers, leaving emotion, indignation and cries for justice to others. They leave others to correlate the data with names, too.

Instead, they offer definitions and analytical tools that add clarity, allow for apples-to-apples comparisons and shed new light on how a leader’s objectives shape company performance.

“It’s possible that high pay is perfectly deserved because of high contributions, high skill sets,” Haynes said, “and just because somebody doesn’t have high pay doesn’t mean they aren’t greedy.”

The marks of greed are found elsewhere—in a reporting category that tracks “other” compensation and perquisites, in the pay rates of other top executives, in compensation demands during times of company stress.

Haynes’ studies included interviews (with anonymity assured), publicly reported data, written surveys, essays and a review of published information and interviews with CEOs.

The studies also examined managerial hubris and how it differs from self-confidence.

“Hubris is an extreme manifestation of confidence, characterized by preoccupation with fantasies of success and power, excessive feelings of self-importance, as well as arrogance,” the researchers wrote.

“Say I’m a stunt driver and I have jumped across five burning cars before with my car,” Haynes said. “I’m pretty confident I can do that—and maybe even six. Say I’m not a stunt driver. To say I could jump through six burning cars would be arrogance. And if I drag you to go with me, it could be criminal.”

Risk aversion can harm a company. But risk for short-term gain without thought of the company’s future is a sign of greed.

“Some CEOs take risks, and it will pay off,” she said. “They will have reliable performance, and we can forecast that. We know their track record. Others take foolish risks not based on their previous performance.”

Such risks may be especially prevalent among young entrepreneurs, who under-estimate the resources needed for a startup to succeed, and fail to recognize that more than money is at stake.

“While financial capital is an important concern with these behaviors, the effects on human and social capital are often overlooked, despite the fact that they are highly critical for the success and ultimate survival of entrepreneurial ventures,” the researchers wrote.

Generally, the team found, greed is worse among short-term leaders with weak boards.

The good news, Haynes said, is that strong corporate governance can rein in CEO greed and keep self-interest and altruism in balance. And that is where the greatest success is found.

“Overall, we conclude that measured self-interest keeps managers focused on the firm’s goals and measured altruism helps the firm to build and maintain strong human and social capital,” the researchers wrote.

MORE STORIES

ADVANCE-ing UD

Seven faculty members are highlighted in this issue of UD Research. Indeed, there are commonalities among them—a steadfast commitment to excellence, unrelenting intellectual curiosity, mentors and role models who inspire, and a disdain for the status quo. I encourage you to read their stories to learn about their inspirations, the challenges they have faced and the scope and quality of their scholarly endeavors.

Women of Research

Extraordinary research is underway at the University of Delaware, and women are all over it. We profile seven researchers who offer insight into their work—from coral reefs to corporations—what hurdles they have cleared and what keeps them moving forward.

Danielle Dixson

A chance encounter with a tour guide at the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago is what sparked Minnesota native Danielle Dixson’s interest in marine biology. “I was 5 years old and the guide gave me a book for asking a clever question about whales,” she says.

Liz Farley-Ripple

Elizabeth Farley-Ripple did not set out to become an education researcher. As an undergraduate at Georgetown University, she started out majoring in Latin American Studies. Then came Professor Bill McDonald’s sociology course focusing on research methods. “I had an aha moment,” says Farley-Ripple. “I realized I could have an impact—and actually apply the ideas I had been reading about.”

Jennifer Joe

Jennifer Joe, the Whitney Family Professor of Accounting in the Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics, attributes positive experiences with her professors in college as the impetus for her pursuit of an academic career.

Rhonda Prisby

Rhonda Prisby had a plan for her master’s degree in exercise physiology. She expected to work in a cardiac rehabilitation clinic. Then a professor mentioned something she hadn’t considered—her potential as a researcher.

Angelia Seyfferth

Having had the chance to conduct research taking water samples on the Chesapeake Bay early in her undergraduate studies, Angelia Seyfferth, assistant professor in the Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, is hoping to pass her enthusiasm for research to young scholars in her lab.

Margaret Stetz

As a scholar with diverse interests from 19th-century British literature to military history and fashion studies, and who shares her work in a variety of academic and community forums, Margaret D. Stetz might be expected to have difficulty summarizing what she does.

Cathy Wu

For Cathy Wu, becoming a bioinformatics expert was kind of accidental. Armed with a Ph.D. in plant pathology and a postdoc in molecular biology, she followed her husband on a job move to Tyler, Texas, in the mid-1980s, but was unable to land a good faculty position there.

Never underestimate the power of good mentoring

A few years ago, a newly hired female faculty member had the following experience: A male colleague responded to her hallway greeting by saying hello and adding, “I hope everyone is making you feel welcome.”

Spin in spins out innovation

The University of Delaware’s “Spin In” program, founded, managed and trademarked by the Office of Economic Innovation and Partnerships, connects University undergraduate students with community entrepreneurs and early-stage startups to give them an inside look at business innovation in action and a chance to apply what they’re learning in real-life situations.

Making it clear

For the past three years, almost 90 educators from around Delaware and Maryland have been working with scientists and environmental experts from the University of Delaware and the University of Maryland. The goal is to develop a richer understanding of climate change and build effective activities and instruction plans to help their students understand the data and find potential solutions.

Solar Strong

The vast majority of the sun’s extraordinary power remains out of reach—absorbed, deflected or otherwise inaccessible to today’s power-hungry masses—but University of Delaware researchers continue their quest to capture more, store more and deploy it more efficiently.

Slaves’ lives emerge from ancient ruins

“Detfri slave of Herennius Sattius” and “Amica slave of Herennius” reads the terra-cotta tile. It was discovered atop the ancient temple in Pietrabbondante, a town tucked into the bare rock and evergreen-covered mountains more than 100 miles east of Rome.

Honors

• Dugan named Truman Scholar

• Overby elected to board of Oak Ridge consortium

• Backbone of the profession

Fearsome Fridays

Tom Fernsler, “Dr. 13,” now retired from the Delaware Center for Teacher Education, knows a lot about Friday the 13th. Do you? Take our quiz and find out!